LIX is a readability measure to score the difficulty of reading a foreign text. The Lix Formula was developed by Swedish scholar Carl-Hugo Björnsson. The formula is as follows:

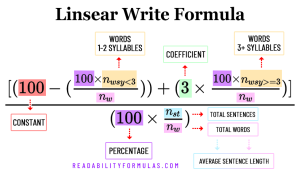

\[\text{LIX} = \frac{\text{Total Number of Words}}{\text{Number of Sentences}} + \left( \frac{\text{Number of Long Words} \times 100}{\text{Total Number of Words}} \right)\]

LIX, the Swedish Readability Formula

Scholars have published three major summaries of readability research in the past 20 years. One summary revealed that countries outside the U.S. have put forth little effort to research and develop readability formulas for foreign text. This summary applied not only to English-reading countries, but to all countries other than the U.S. Another academic report revealed that Mexican researchers applied American readability formulas to foreign language texts to assess a reading-level for their texts.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, as of 2018, nearly 22% of U.S. students come from homes where a language other than English is spoken. This highlights the growing need for text readability tools in multiple languages.

During the last decade the United Kingdom Reading Association published a book, entitled “Readability.” The most recent work on readability, also from the United Kingdom, is Colin Harrison’s “Readability in the Classroom.” Again, surprisingly, these publications do not talk about the problem of scoring readability of non-English materials.

“In an era of globalization, understanding the nuance and subtlety of language across cultures and borders is more than a skill—it’s a necessity,” said Prof. Iman Aoun, an expert linguistic anthropologist.

Education has rapidly grown into a multicultural society. The lack of foreign language readability formulas is a problem. And yet there is one readability formula, developed in Sweden, which holds promise for scoring text difficulty in other languages including English.

A few years before the release of Gilliland’s book, Readability, Carl-Hugo Björnsson (1968) published a book entitled Lasbarhet (which, translated to English, is entitled “Readability“). Björnsson’s book is not well-known outside Sweden (no doubt because few people know Swedish), yet classroom teachers will find the formula useful.

Björnsson developed his readability formula by selecting 12 features of text (known to influence reading difficulty), and measuring each of these across 18 books in each of the 9 levels of the Swedish comprehensive school (i.e., 162 books in all). In the final step, he used the traditional regression approach to score the difficulty of text judged by teachers and students.

Björnsson tested the 12 readability factors against such benchmarks as validity, reliability, objectivity, and ease of processing. Björnsson, like other researchers before him, found that he could use two factors—a word factor and a sentence factor—to predict readability accurately. He called his readability index “Lasbarhetsindex” which was shortened to LIX.

The word factor in LIX is length; however, it is measured differently. Rather than syllable count, polysyllabic words, or unfamiliar words as judged by a word list, LIX scores word length by the percentage of long words (i.e., words of more than six letters like the Raygor Readability Graph). Gauging words makes LIX more objective and quicker to score than other formulas. The sentence factor (sentence length) is the average number of words per sentence, as in the Flesch, Spache, Fry and other measures of readability. Finally, word and sentence factors are weighted equally.

According to the Ethnologue, as of 2022, over 40% of the world’s population is bilingual, and 13% is trilingual, reinforcing the importance of effective multilingual communication tools.

Comparing French and English Texts with LIX

A graduate student at Flinders University tested LIX with French and English texts. This was an independent project undertaken as part of the Diploma in Education. The graduate student selected 10 books of fiction used in upper primary and lower secondary school. The books, however, were selected because of the availability of a translation in the other language. Some books were English titles for which a French translation existed, while others were French titles for which an English translation existed. The student selected random samples of text from each book and then identified parallel samples in the translation.

To test LIX’s accuracy, the student calculated indices for each title in both French and English. The indices included Björnsson’s advice of selecting a 2000-word sample (made up of 20 100-word samples) and a separate sample of 200 sentences (20 samples each of 110 sentences).

To compare these estimates of reading difficulty with other acceptable measures, the student applied Flesch’s Reading Ease Formula over the 2000-word sample from each title, in both languages. Flesch’s formula was judged appropriate for the difficulty levels of the texts.

The results are interesting: LIX indices in French correlated 0.87 with LIX indices in English; while Flesch indices across languages correlated 0.90. Both correlations suggested that the factors being measured in French and English by these two formulas were very similar. When LIX and Flesch were correlated over the French books, the correlation was -0.80, while over the English books was -0.78 (the negative results exist because difficulty is rated high on LIX, but low on Flesch). Because Flesch provides a valid measure of text difficulty, then LIX would appear to measure text difficulty similarly.

A report by the International Telecommunication Union in 2023 indicated that over 50% of the world’s population read online in multiple languages, underlining the importance of multilingual readability in digital content.

How to Interpret Lix Readability Formula

To illustrate how you can apply and interpret LIX, let’s use these two samples: the Tax Act and the Very Bad Day.

SAMPLE 1:

SAMPLE 2:

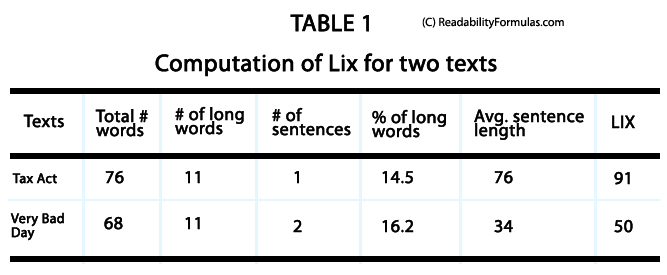

Calculate as follows:

1. Count for each text

(a) the total number of words,

(b) the number of long words (i.e. words of more than 6 letters), and

(c) the number of sentences.

2. Compute word length (percentage of long words):

divide (b) by (a) and multiply by 100.

3. Compute sentence length (average length of sentences in words):

divide (a) by (c).

4. Add the two values obtained in (2) and (3) and round to the nearest whole number.

These calculations are shown in Table 1.

The calculations show how easy you can compute LIX. In the two sample texts, sentence length added more than word length to the total score ( 84% of Lix for the Income Tax text and 68% of LIX for the Very Bad Day text). Also, you can easily interpret the word and sentence factors. The word length of 14.5 (Income Tax) means that about one in seven words is a long word; and the word length of 16.2 (Very Bad Day) means that every sixth word is a long word. Just as word length have meaning, so does sentence length. In the Income Tax text, sentence length shows that the average length is 76 words while in the second text it averages 34 words .

Other factors add to reading difficulty, such as 1) factors within the reader; 2) the purpose for which the texts are written; and 3) how readers interact with the text. LIX, like other readability measures, provides only an inexact and incomplete estimate of reading difficulty. Like any information (e.g., content, form and layout), you need to evaluate the text.

Björnsson created the following table to interpret LIX scores. These norms are for Swedish; currently, there are no similar norms to interpret scores in other languages, except for French, German and Greek.

| Interpreting Lix Scores (Swedish texts) | |

| Text Difficulty | Lix |

| Very Easy | 20—25 |

| Easy | 30—35 |

| Medium | 40—45 |

| Difficult | 50—55 |

| Very Difficult | 60— |

The two sample texts above are very short (one and two sentence respectively). Do not generalize with samples of this size. Nevertheless, you can find consistencies which suggests you can use LIX across other languages and at a variety of levels — from young children’s materials through to secondary level and adult texts.

According to Eurostat, in 2019, over 80% of students at the upper secondary level in the European Union were studying at least two foreign languages. This emphasizes that we need readability tools for diverse texts.

Globalization has changed how countries use language. More people speak multiple languages, so we must make content clear for different groups. The challenge is not only language—but also culture. While tools like LIX can measure text readability, we also need to understand cultural differences, idioms, and local expressions. We need researchers from linguistics, cognitive science, and cultural studies to work together to ensure our texts resonate and make sense to readers.

Scott, Brian. “Lix Readability Formula: The Lasbarhetsindex Swedish Readability Formula.” ReadabilityFormulas.com, 20 Nov. 2024, https://readabilityformulas.com/the-lix-readability-formula/.