The New Dale-Chall Readability Formula has improved readability scoring, building upon the foundation laid by its predecessor. The (original) Dale-Chall Readability Formula, developed by Edgar Dale and Jeanne Chall in the 1940s, became a standard in scoring text readability. It helped match reading materials to the learners’ reading abilities, ensuring their understanding and promoting further reading. The formula is based on difficult words and average sentence length. While the original formula was useful, it did not capture syntactic complexity and word familiarity.

The New Dale-Chall Readability Formula addresses the original formula’s shortcomings. Chall improved linguistic and syntactic features, along with an expanded and updated list of familiar words. The Chall Word List, as it is known, identifies words that may challenge readers.

The formula scores a text using these steps:

- Word Identification: The formula identifies words absent in the word list. These words are considered “difficult words” because readers might find them challenging.

- Difficult Words Count: The number of difficult words is tallied.

- Sentence Count: A longer “average sentence count” could imply more intricate sentences, impacting the text’s overall readability. This factor extends the complexity assessment beyond just vocabulary.

- Familiar Words Adjustment: The number of difficult words is divided by the total word count, and the result is multiplied by 100 to give the percentage of difficult words.

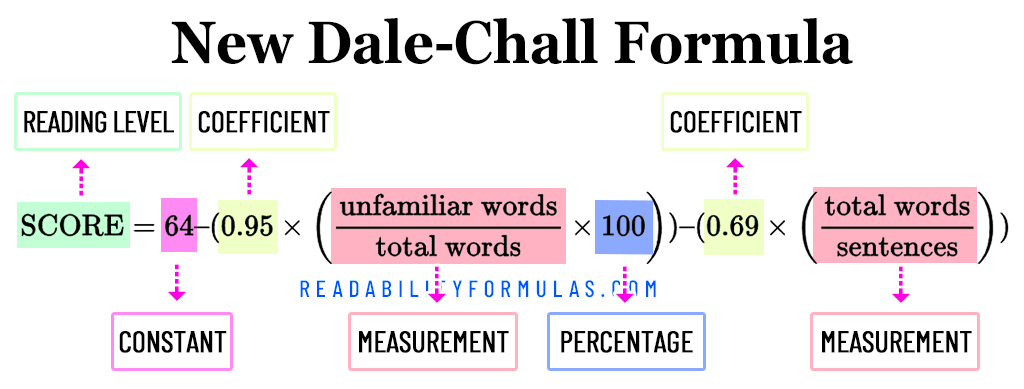

The new formula is as follows:

$$\text{SCORE} = 64 – (0.95 \times \left( \frac{\text{unfamiliar words}}{\text{total words}} \times 100 \right)) – (0.69 \times \left( \frac{\text{total words}}{\text{sentences}} \right))$$

- Unfamiliar Words are defined as 2+ syllable non-sight words.

- Total Words is the total number of words in the text.

- Sentences is the number of sentences in the text.

What Does the Score Mean?

| Bormuth/Dale-Chall Reading Scale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score Range | Difficulty | Age | Grade | Grade Range |

| 58+ | Extremely Easy | 5-6 years | 1 | 1 |

| 57 – 54 | Very Easy | 7 years | 2 | 2 |

| 53 – 50 | Fairly Easy | 8 years | 3 | 3 |

| 49 – 45 | Easy | 9 years | 4 | 4 |

| 44 – 40 | Average | 10-11 years | 5-6 | 5.5 |

| 39 – 34 | Average – Slightly Difficult | 12-13 years | 7-8 | 7.5 |

| 33 – 28 | Slightly Difficult | 14-15 years | 9-10 | 9.5 |

| 27 – 22 | Fairly Difficult | 16-17 years | 11-12 | 11.5 |

| 21 – 16 | Difficult | 13 – 15 years | College Student | 14 |

| 15 – | Very Difficult | 18+ | College Graduate | 16 |

What Are Constants, Coefficients, and Measurements — And Why Do They Matter?

1. Constant (64)

This is the starting score. If a text has zero unfamiliar words and very short sentences, the score begins at 64, which represents extremely easy text.

Why 64?

Jeanne Chall and Edgar Dale wanted the formula to reflect the natural upper limit of readability for basic, familiar writing. They tested thousands of texts across grade levels and found that most very simple texts (like those using only familiar vocabulary) hovered around this score.

2. Coefficients (0.95 and 0.69)

These are the weights that tell the formula how much each factor matters.

0.95: Applied to the percentage of unfamiliar words

A higher number here means difficult vocabulary lowers the score significantly.

0.69: Applied to the average sentence length

Long sentences also reduce readability, but slightly less than unfamiliar vocabulary.

Why these numbers?

Chall and Dale ran statistical analyses on how well different features predicted reading difficulty. They discovered that vocabulary difficulty had a stronger impact on comprehension than sentence length. So, they gave unfamiliar words more weight ( 0.95 vs. 0.69 ).

3. Measurements (What the Formula Analyzes)

Unfamiliar Words ÷ Total Words × 100

This tells us what percentage of words are likely unfamiliar to the average reader.

Total Words ÷ Sentences: This gives the average sentence length, which is linked to syntactic complexity. These values are pulled directly from the text. They change depending on what you’re analyzing.

Jeanne Chall and Edgar Dale didn’t just guess these numbers — they based them on years of research, classroom testing, and statistical analysis. Their goal was to help educators and writers make sure that reading materials were appropriate for their audience.

Thanks to their work, we still use this formula today to judge whether writing is too simple, too complex, or just right — based on the balance of word familiarity and sentence structure.

New Dale-Chall scored NEW MOON, the 2006 romantic fantasy novel by author Stephenie Meyer, at a 5th-6th reading grade level, which is the reading level validated by teachers and literary specialists. You can see the results below.

Dale-Chall is useful for educators, publishers, and writers. They can use it to choose reading materials that match the audience’s reading skills. The formula’s standard and unbiased measure of text complexity aids in effective literacy. However, like all formulas, the Dale-Chall formula is limited. Text assessment is more than just a numbers-based approach.

Let’s look at what else matters:

- Content Relevance: Text should matter to the reader. Even simple writing may confuse if it discusses unfamiliar or dull topics. But, a complex topic can grip a reader if it speaks to their interests.

- Reader Motivation: The reader’s eagerness to learn affects understanding. An excited reader will try harder to grasp tough content. Engaging and inspiring text is crucial.

- Learning Styles: Everyone absorbs information differently. Some lean towards images, others prefer words or sounds. These preferences play a part in judging a text’s complexity.

- Background Knowledge: Familiarity with the subject shapes the reader’s grasp of the text. Unknown terms or concepts can stump them, no matter how readable the text is.

- Cultural References: Texts often use idioms or references known only to certain cultures. These can hinder understanding for others.

- Text Structure: The layout of a text affects its readability. Clear headings, bullet points, diagrams, and logical flow can aid comprehension.

- Language Nuances: Tricky language devices like irony or sarcasm can make comprehension harder. These aren’t covered by readability formulas but can influence understanding.

While readability tools can be useful, writers still need to review the overall text’s complexity and the target audience’s needs.

At ReadabilityFormulas.com, you can score your text using both the original and updated versions of Dale-Chall, or select from a range of syntactic, word-based, and graph-based formulas.

Scott, Brian. “Learn about the New Dale-Chall Readability Formula.” ReadabilityFormulas.com, 20 May. 2025, https://readabilityformulas.com/learn-about-the-new-dale-chall-readability-formula/.