Imagine you’re at a bustling international airport. A sign overhead reads, “To Gates and Flights.” It’s concise, uses familiar words, and based on traditional readability formulas, it’s clear. But then, consider a traveler named Aisha, visiting from a country where she’s used to icons and symbols rather than word signs. To her, words like “gate” and “flight” are unfamiliar. She pauses, looking for symbols of planes or an arrow; she tries to decode the sign’s message amidst the sea of rushing passengers.

Imagine you’re at a bustling international airport. A sign overhead reads, “To Gates and Flights.” It’s concise, uses familiar words, and based on traditional readability formulas, it’s clear. But then, consider a traveler named Aisha, visiting from a country where she’s used to icons and symbols rather than word signs. To her, words like “gate” and “flight” are unfamiliar. She pauses, looking for symbols of planes or an arrow; she tries to decode the sign’s message amidst the sea of rushing passengers.

Years ago, when Aisha was starting to learn English in 12th grade, her teacher handed out a pamphlet titled “Easy English for Beginners.” The content, filled with short sentences and basic vocabulary, had a readability score of 7th grade. However, she stumbled over cultural idioms and phrases. The phrase “it’s raining cats and dogs” made her chuckle as she wondered why pets would be associated with rainfall.

This airport sign and Aisha’s classroom memory remind us that understanding a piece of text isn’t solely about complex words or sentences. It’s a nuanced dance between the text and the reader, colored by the reader’s cultural background, experiences, and prior knowledge.

Written words are more than letters in sentences. Aisha’s experience at the airport and her classroom challenges show that reading is an active process. Readers don’t passively receive information; they engage with the text—they embrace their own perspectives, experiences, and cultural backgrounds. If we rely on formulas to judge our writing’s clarity, we might overlook the unique ways each reader interacts with a text. To truly understand how clear and accessible our writing is, we need to consider the reader’s active role.

The Problems with Readability Formulas

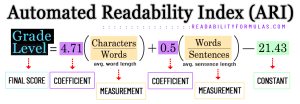

Readability formulas are objective calculations used to score the difficulty of reading a text—they’re based on syntactic factors, such as sentence length and word syllables. Most formulas output a U.S. grade level. These formulas take on a “one-size-fits-all” approach: you can use the same formula to score any text for any reader for any purpose. This generic approach implies readers process information uniformly and passively, word by word, sentence by sentence. But modern readers are not passive text-processing machines. Nor do they process text linearly when reading digital content. We all approach reading in an active way—in different ways. We search for meaning. We bring our attitudes, interests, knowledge, and experiences to bear on what we read.

While formulas assume longer words are less familiar and harder to read than shorter ones, we can find exceptions to this rule. For example, the reader’s familiarity with the subject matter counts for a lot. A meta-analysis by Crossley, Greenfield, and McNamara challenged the notion that longer words and sentences are more challenging. They concluded that factors like word concreteness, familiarity, and semantic difficulty impact readability, more so than the length of words or sentences.

| Text Problems | Solution |

| Lack of context sensitivity and semantic nuance | Use context cues, activate prior knowledge, and explain terms within the text’s context. |

| Cultural biases and insensitivity | Review text for cultural inclusiveness, use universal examples, and avoid idioms. |

| Failure to engage and direct the reader | Use compelling hooks, clearly state benefits and provide explicit calls-to-action. |

| Oversight of modern reading patterns (skimming/scanning) | Design content to skim—with headings, bullet points, and key highlights. |

| Ignores non-linear digital reading | Use navigational aids; ensure multimodal elements support text comprehension. |

| Uses only readability scores and grade levels to determine text difficulty | Use scores as a guide, but also conduct user testing and seek feedback for improvement. |

| Ignores reader motivation and interest | Tailor content to readers’ interests and motivations to increase engagement. |

| Assumes one metric fits all genres and formats | Adapt readability assessments to different genres and formats; recognize their unique challenges. |

| Neglects the role of text structure and organization | Use clear and logical text structures, with coherent organization and flow of ideas. |

| Overlooks reader’s prior knowledge on topics and subjects | Assess reader’s prior knowledge and scaffold information accordingly. |

| Ignores the emotional tone and its impact on readability | Consider the emotional tone and how it may affect reader engagement and understanding. |

| Overlooks readers’ goals | Align text content with reader goals for greater relevance. |

| Underestimates the visual presentation of text | Enhance readability with visual aids, font sizes and choices, and line spacing. |

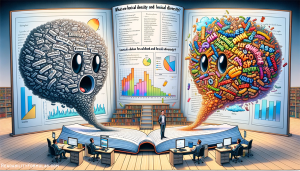

The two examples below point out that not all content with the same readability score is equally easy to understand. Both examples have short sentences and mostly short words, and the same readability score. But which example is easier to understand and do?

Example #1:

2) Now put down your middle initial and your last name.

3) Fill in your age on the next line.

— and —

Example #2:

2) Add all your assets in real estate, stocks, and bonds.

3) Figure your tax from the table.

The examples highlight a problem: a grade level score does not tell you if readers can understand and use your material as it is intended. Other flaws: 1) formulas can’t tell you if your text is clear and effective to the target readership; 2) if it will attract and hold your readers’ attention; or 3) if it is culturally-appropriate.

With the reader in mind, review your text and ask the following:

1. Readers prefer to skim or scan text to glean information. Omit any overpowering “wall of text.” Avoid small print or poor color contrast. Ensure the layout doesn’t look too busy or confusing or complicated. Use short paragraphs, with clear headings and bullet points. Select the font size and color contrast to enhance readability.2. Don’t force unfamiliar words onto the reader. Organize information to explain things more cohesively. Use straightforward language. Avoid jargon or complex words where simpler ones suffice. Clearly explain any necessary technical terms.A study by the University of California, San Diego suggests that the average American encounters anywhere from 100,000 to 1,000,000 words every day. Given this information overload, it’s easy to see why readers prefer to skim rather than read every word.

3. Your readers may be in a hurry, distracted, or stressed. This can affect their concentration and reading speed. Aim for conciseness. Sentences should be clear, to the point. Convey information with efficiency. Paul Graham , a prolific and renowned essayist, says, “Simple writing is persuasive. A good argument in five sentences will sway more people than a brilliant argument in a hundred sentences. Don’t fight it.” 4. Readers may not find your text interesting or appealing at first glance; or the reader begins reading it and then loses interest. To hook your readers, introduce a compelling hook or a relatable scenario. It’s important to catch attention early. A good hook is like the first line of a chess game. It leads to an inevitable series of events that will define everything that comes after it. 5. Your information might be culturally unsuitable. Readers can’t relate to it; they don’t feel respected or understood; or they feel put off or offended. For example: Using idioms such as “kill two birds with one stone” may be misunderstood in cultures that value animal life. Or describing something “as American as apple pie” neglects the diversity of readers and their culinary traditions. Be mindful of cultural biases. Use examples and language that includes and respects all readers.According to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy , only 13% of American adults have proficient literacy. This statistic highlights the need for clear, accessible writing that they can understand at different levels of literacy.

A study found that learners of English as a second language need to know about 4,000 to 5,000 word families to understand everyday texts. This becomes more challenging when idiomatic expressions are included, which often require cultural context to comprehend. ( Nation, 2016 )

6. Readers can’t figure out how to use your information or what it’s for. They see no benefit from reading it; or they find the action it calls for too difficult or unrealistic. To avoid these issues, clearly state its intent in the opening sentence or paragraph. Outline the benefits of reading your text. Include realistic calls-to-action and clearly explain what to do.

Remember: The reader is the one who decides what is worth reading. It’s also the reader—not a grade level score—who decides if the material is easy to understand and use.

Avoid the mistake of relying too much on a grade level score as the only criterion as this can mislead you into thinking your readers can read and comprehend your text.

Scott, Brian. “Readability Formulas and the Active Role of the Reader.” ReadabilityFormulas.com, 20 Nov. 2024, https://readabilityformulas.com/readability-formulas-and-the-active-role-of-the-reader/.