In the pursuit of clear and effective writing, nominalizations stand out as a common yet often overlooked pitfall. Robert Gunning, in his influential book “The Technique of Clear Writing,” highlighted the negative impact of nominalizations on readability and engagement. He said nominalizations—verbs turned into abstract nouns—were a major culprit in making writing difficult to read.

Which sentence do you understand?

- Sentence 1: “All employees must ensure the submission of their timesheets by the end of the working day on Friday to help HR with the facilitation of processing payroll.”

- Sentence 2: “Employees must submit their timesheets before they leave on Friday so HR can process payroll.”

Both sentences mean the same, but Sentence 2 uses direct verbs, not nominalized ones. These small changes in a sentence make a big difference. Sentence 2 is easier to read; it’s direct, less abstract, and less complex—precisely what today’s readers want.

What Are Nominalizations?

Nominalizations occur when the writer transforms verbs or adjectives into nouns using suffixes such as -tion , -ment , -ness , and -ity . You’ve come across them in all types of texts, from academic writing to short stories. For example, the verb “decide” becomes “decision” and “analyze” becomes “analysis.”

Verb: to analyze → Noun: analysis

Action: The scientist analyzed the samples in the lab.

Nominalized: The scientist’s analysis of the samples revealed important findings.

Adjective: curious → Noun: curiosity

Description: The child was curious about how rainbows form.

Nominalized: The child’s curiosity about how rainbows form led to many questions.

Nominalizations impact writing at the syntactic level. This includes word length, syllable count, sentence length, cognitive reading load, passive vs. active voice, and easy words.

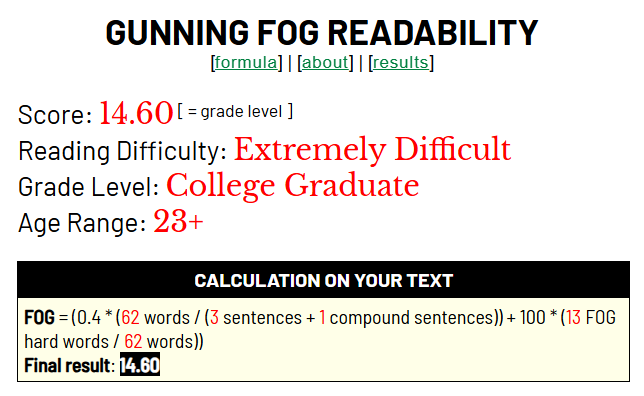

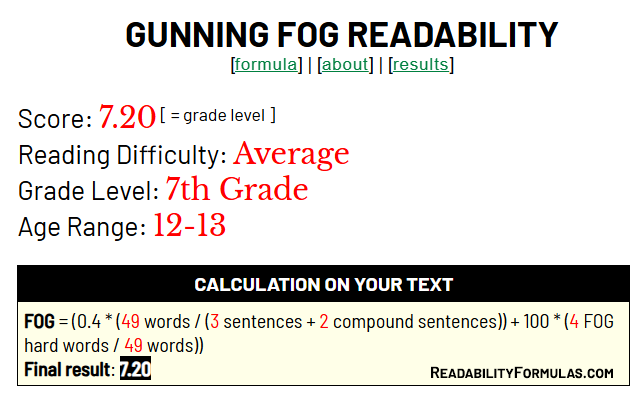

Before

(With Nominalizations):

The creation(3) of a healthy eating plan can have a significant enrichment(3) on your overall well-being. Doctors say the reduction(3)of processed foods and the consumption(3) of fresh fruits and vegetables can lead to an improvement(3) in energy levels and a prevention(3) of chronic diseases. The achievement(3) of a balanced diet is not always easy, but the results will be beneficial(4).

* Syllable count in parenthesis.

After

(Without Nominalizations):

If you want to enrich(2) your well-being, create(2) a healthy eating plan. Doctors say if you reduce(2) processed foods and consume(2) fresh fruits and vegetables, you can improve(2) your energy and prevent(2) chronic diseases. It’s not easy to achieve(2) a balanced diet, but the results will benefit(3) you.

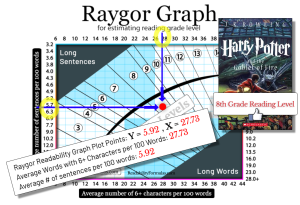

The example without nominalizations scored a 7th grade reading level: it reads quicker, clearer, and simpler. Let’s see why:

1. Word Length: nominalizations increase word length compared to their verb or adjective counterparts. Ex: “Enrich” (6 letters) becomes “enrichment” (10 letters). Changing the verb into a noun adds the suffix -ment, increasing word length.

2. Syllable Count: nominalizations have more syllables than their root forms. Ex: “Benefit” (3 syllables) becomes “beneficial” (4 syllables). This makes the word more complex to pronounce and understand.

3. Sentence Length: nominalizations can lead to longer sentences. Every sentence with nominalizations became longer. This is because nominalizations need extra words to form grammatically correct sentences.

4. Cognitive Reading Load: nominalizations increase cognitive load on readers. They need to process more complex sentences and abstract concepts, which can slow down reading and comprehension. Abstract nouns are harder to process than concrete verbs as they require more mental effort to understand the action being described.

5. Passive vs. Active Voice: nominalizations lead to passive voice. Ex: “It’s not easy to achieve a balanced diet, but the results will benefit you.” (active) vs. “…but the results will be beneficial” (passive). Passive constructions can make sentences less direct and harder to read.

6. Easy Words Turned Hard: nominalizations can turn simple words into complex ones. Ex: “consume” becomes “consumption,” “achieve” becomes “achievement.” In scoring readability, 2-syllable words are scored “easy” while more syllables are scored “hard.” Most nominalizations are scored “hard.”

Formality Over Simplicity

If the best type of writing for public readers is Plain English, why do writers use or abuse nominalizations? Are they too lazy to self-edit? Do they not know their readers? Do they not care if nominalizations might confuse their thinking? Here are the most common reasons why:

1. Perceived Authority: In many professional, academic, and legal contexts, writers use nominalizations to sound formal and authoritative. Nominalized forms can make the text appear and sound more sophisticated, serious, and credible. They write to impress, not to express. Ex: “The implementation of new policies” sounds more formal than “implementing new policies.”

2. Habit and Tradition: Many fields, such as law, academia, and business, have long-standing centuries-old traditions of using formal, nominalized language. Writers in these fields follow established norms and styles, without considering the impact on readability. In fact, legal style guides include nominalizations as part of the conventional style, thus emphasizing formality over simplicity. In academic writing, professors encourage students to use nominalizations to discuss theories and concepts. Ex: “The evaluation of the theoretical framework” follows academic style more closely than “Let’s evaluate this theory.”

3. Lack of Responsibility: Overuse and abuse of nominalizations appear in policy-making and politics. Nominalizations create an impersonal tone by removing the actor from the action. This can be useful in bureaucratic or diplomatic language where the writer wants to avoid assigning direct responsibility. Ex: “The manager failed to inform the team about the changes” is changed to “The failure to inform the team about the changes was noted.”

4. Abstraction and Generalization: Nominalizations can turn specific actions into abstract concepts, which is useful to discuss ideas at a higher level of generality. This is common in academic, scientific, and technical writing, where the focus is on broader concepts rather than specific actions. Original: “Engineers are designing new software to improve data security.” Nominalization: “The design of new software for data security improvements is in progress.”

5. Complex Ideas: When handling complex subjects, nominalizations can convey intricate relationships and ideas succinctly. For example, in scientific writing, nominalizations can help encapsulate complex processes or phenomena. Original: “Engineers are developing new technologies to improve renewable energy.” Nominalization: “The development of technologies to enhance renewable energy efficiency is advancing.”

6. Passive Voice Preference: Nominalizations often create passive voice—a technique to emphasize the action over the actor. This is common in scientific and technical writing when writers want to focus more on the process or result rather than who performed the action. Ex: “The data was analyzed by the scientists” rather than “The scientists analyzed the data.”

7. Compactness: Nominalizations can condense complex actions into a single term, making it easier to reference them without repeating the full explanation. Ex: “The researchers conducted a series of experiments to determine the effects of the new drug on the immune system.” Nominalization: “The researchers’ experimentation determined the effects of the new drug on the immune system.” In the nominalized sentence, “experimentation” condenses the phrase “conducted a series of experiments.” This nominalization makes the sentence more compact and easier to reference repeatedly.

8. Avoiding Repetition: To avoid repetitive use of verbs, writers use nominalizations to vary sentence structure. This can make the text seem more sophisticated, even if it becomes less clear. Ex: Alternating between “the analysis” and “analyzed.”

9. Jargon: Certain fields, especially technical and scientific ones, have a lot of jargon that includes nominalizations. Writers in these fields might use them to conform to the expected language. Ex: “The optimization of algorithms” is common in technical writing.

10. Consistency: Writers may use nominalizations, especially in technical writing, to convey complex information uniformly. (Action) “The engineer designed the system, tested its components, and implemented the final version.” (Nominalization) “The engineer’s design, testing, and implementation of the system ensured its success.”

In the action sentence, the writer uses different verb forms (designed, tested, implemented) to describe the actions. This variety in verb forms can disrupt the sentence’s consistency. In the nominalized sentence, the writer nominalizes the actions (design, testing, implementation) to create a parallel structure in the sentence.

Striking a Balance

To maintain readability, strike a balance between nominalizations and active verbs. Use nominalizations to enhance clarity, add necessary formality, or to discuss abstract concepts. Avoid nominalizations when they obscure the main action, make sentences verbose, or reduce directness and engagement.

If you write for one of these genres, then remind yourself not to overuse nominalizations.

Creative Writing: Creative writing, including fiction, poetry, and personal essays, relies on vivid imagery and dynamic action to engage readers. Nominalizations can make the text feel static and impersonal, detracting from the emotional impact and narrative flow.

Example:

- Nominalizations: “The observation of the sunset was a source of great inspiration for her. The realization of her dreams seemed more attainable in this moment of reflection.”

- Balanced Use with Active Verbs: “She watched the sunset, feeling inspired by its beauty. In that moment, she felt she could attain her dreams as she reflected on her journey.”

In the first version, the nominalizations “observation,” “realization,” and “reflection” make the sentences feel static and detached. The second version, using active verbs like “watched,” “feeling inspired,” and “reflected,” creates a more dynamic and emotionally engaging narrative.

Journalism: News articles and feature stories need to convey information clearly and quickly. Readers expect direct and concise language. Nominalizations can slow down reading and make the writing seem too formal or convoluted.

- Overuse: “The initiation of the investigation was announced by the police.”

- Better: “The police announced they have begun the investigation.” OR: “The police started to investigate.”

Business Communication: Memos, emails, and reports should be clear and actionable. Nominalizations can make instructions and information less direct, leading to misunderstandings or inefficiencies.

Example:

- Overuse: “The implementation of the new software will commence next week.”

- Better: “We will start using the new software next week.”

Technical Writing: Manuals, guides, and technical documents need clear instructions and explanations. While some nominalizations are unavoidable, overuse can make the text dense and difficult to follow.

Example:

- Overuse: “The configuration of the system requires attention to detail.”

- Better: “Configuring the system requires attention to detail.”

Marketing and Advertising: Marketing copy and advertisements aim to persuade and attract buyers. They should be engaging and easy to read. Nominalizations can make the message feel distant and less compelling.

Example:

- Overuse: “The introduction of our new product line is the enhancement you need in your lifestyle.”

- Better: “Our new product line will enhance your lifestyle.”

Educational Materials: Textbooks, lesson plans, and educational content should be accessible and easy to understand for learners. Overusing nominalizations can obscure meaning and make the material harder to comprehend.

Example:

- Overuse: “The simplification of the equation is necessary for solving the problem.”

- Better: “You need to simplify the equation to solve the problem.”

Web Content: Articles, blog posts, and other web content need to be clear and engaging to retain readers’ attention. Nominalizations can make the content less dynamic and harder to read, which is a problem in a medium where readers often skim text.

Example:

- Overuse: “The improvement of site speed is critical for user retention.”

- Better: “Improving site speed is critical for keeping users.”

Readers Who Hate Nominalizations

A study by the National Literacy Foundation revealed that a common writing habit—overusing nominalizations—can hinder comprehension for many readers, from young students to non-native English speakers, and even casual readers. Understanding the challenges these groups face can help writers create more effective, engaging, and inclusive content.

Young Readers (Elementary to Middle School Students): Young readers are developing their reading skills and vocabulary. Nominalizations can make the text more challenging to understand, as these readers may struggle with abstract nouns and complex sentences.

Non-Native English Speakers (ESL/EFL Learners): Learners of English as a second or foreign language find it easier to understand direct and straightforward language. Nominalizations can add unnecessary complexity, making it harder for them to grasp the text’s meaning.

General Public: When writing for the public, clarity and readability are paramount. The general public includes readers with different levels of education and language skills. Too many nominalizations can alienate or confuse these readers. The average readability level for public readers is 8th grade.

High School Students: While high school students have more advanced reading skills than younger students, they still benefit from clear and direct language, especially when learning new concepts. Overusing nominalizations can make educational content less accessible.

Readers with Learning Disabilities: Readers with learning disabilities, such as dyslexia, can better read and understand texts that use clear, straightforward language. Nominalizations can add layers of difficulty that impede comprehension.

Casual or Recreational Readers: Readers who read for pleasure rather than academic or professional reasons prefer simple, engaging, and concise content. Nominalizations can make the text feel dense and less enjoyable.

Lower Literacy Levels: Readers with lower literacy levels may struggle with complex sentences and abstract concepts. Keeping language simple and direct helps make the text accessible to everyone.

Refer to the following table to remind yourself about not overloading your readers with nominalizations.

| Grade Level | Percentage of Nominalizations | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Grade | 0-2% | Young readers need simple, clear language to develop basic reading skills. |

| 2nd Grade | 1-3% | Focus on simple sentences and direct language to build foundational literacy. |

| 3rd Grade | 2-4% | Gradual introduction to more complex sentence structures while maintaining clarity. |

| 4th Grade | 3-5% | Encourage clear and straightforward writing to improve comprehension. |

| 5th Grade | 4-6% | Incorporate slightly more complex ideas, but keep language direct and clear. |

| 6th Grade | 5-7% | Balance between introducing more abstract concepts and maintaining readability. |

| 7th Grade | 6-8% | Students are ready for more abstract language, but clarity should still be a priority. |

| 8th Grade | 7-9% | Allow for a bit more complexity in sentence structure, ensuring comprehension is not compromised. |

| High School (Grades 9-10) | 8-10% | Students can handle more complex and abstract ideas, but clarity is still important. |

| High School (Grades 11-12) | 9-12% | Increased use of nominalizations to discuss more complex ideas while maintaining readability. |

| College Undergraduate | 10-15% | Higher level of reading proficiency allows for more abstract and complex language. |

| College Graduate | 12-20% | Advanced readers can manage complex and abstract language, but excessive use can still hinder readability. |

Examples of Public-Facing Documents

A key principle in Gunning’s book is to “put action in your verbs.” Direct verbs make sentences more dynamic and clear. As you edit your final draft, identify words ending in suffixes like -tion, -ment, -ness, and -ity. These often hide nominalizations. Replace them with their verb forms to make sentences more direct and dynamic.

1.

Public Notices and Announcements

Source: NYC Parking Regulations Notice

Original: “The implementation of new parking regulations will commence on July 1. Compliance with these regulations is mandatory to avoid penalties. The enforcement of these regulations will be monitored by the city authorities, and violations will result in fines.”

Readability Score: 12th Grade | Reading Level: Difficult

Plain English: “New parking rules start July 1. Please follow these rules to avoid penalties. City authorities will monitor these rules; if you break them, the City will fine you.”

Readability Score: 6th Grade | Reading Level: Fairly Easy

2.

Legal Documents and Forms

Source: IRS Tax Forms and Instructions

Original: “The submission of this form must be completed by June 15 to ensure compliance with federal regulations. Failure to adhere to this deadline will result in penalties and interest charges. The provision of accurate information is crucial to avoid any legal complications.”

U.S. Grade Level: 12th Grade | Reading Level: Difficult

Plain English: “Please submit this form by June 15 to follow federal rules. If you miss this deadline, you will have to pay extra fees and interest. Make sure your information is correct to avoid any legal problems.”

U.S. Grade Level: 6th Grade | Reading Level: Fairly Easy

3.

Health and Safety Information

Source: CDC Health Advisories

Original: “The distribution of the health advisory will occur tomorrow. The objective of this advisory is the prevention of disease spread by informing the public about necessary precautions. The adherence to these guidelines is essential to maintain public health and safety.”

U.S. Grade Level: 12th Grade | Reading Level: Difficult

Plain English: “We will send out the health advisory tomorrow. This advisory will inform the public about how to prevent disease spread. These guidelines aim to keep everyone healthy and safe.”

U.S. Grade Level: 8th Grade | Reading Level: Average

4.

Educational Materials and Instructions

Source: Department of Education Guidelines

Original: “The evaluation of student performance will be conducted next week. The objective of these evaluations is to assess the academic progress of students. The participation of all students in these evaluations is mandatory to ensure comprehensive data collection.”

U.S. Grade Level: College Level Entry | Reading Level: Very Difficult

Plain English: “Dept. of Ed. will evaluate students’ academic progress next week. All students must be present so we can collect ample data.”

U.S. Grade Level: 6th Grade | Reading Level: Fairly Easy

5.

Government Reports and Summaries

Source: EPA Environmental Reports

Original: “The investigation into the environmental impact of the project resulted in several recommendations. The implementation of these recommendations is necessary to mitigate adverse effects. The collaboration with local authorities will facilitate the enforcement of these measures.”

U.S. Grade Level: College Graduate | Reading Level: Extremely Difficult

Plain English: “We reviewed the project’s impact on the environment and advised how to reduce adverse effects. Working with local agencies will help enforce these measures.”

U.S. Grade Level: 8th Grade | Reading Level: Average

6.

Citizen Guides and Handbooks

Source: Federal Election Commission Voter Guide

Original: “The verification of voter identity will be required at the polls. The submission of absentee ballots must be completed by the deadline. The provision of accurate voter information is essential to maintain the integrity of the election process.”

U.S. Grade Level: 12th Grade | Reading Level: Difficult

Plain English: “Show your ID at the polls or submit an absentee ballot by the deadline. Accurate voter information is needed to ensure a fair election process.”

U.S. Grade Level: 8th Grade | Reading Level: Average

Robert Gunning always reminded writers that “Clear writing means clear thinking…The best writing is not for keeping the reader in the dark, but for showing them the light.” Whether writing for young students, non-native speakers, or seasoned professionals, let clear thinking guide your writing style. As Gunning aptly put it, “Writing is thinking on paper…If your words are not clear, you might as well be talking to yourself.” Let’s commit to thinking—and writing—clearly to ensure your words resonate and inspire.

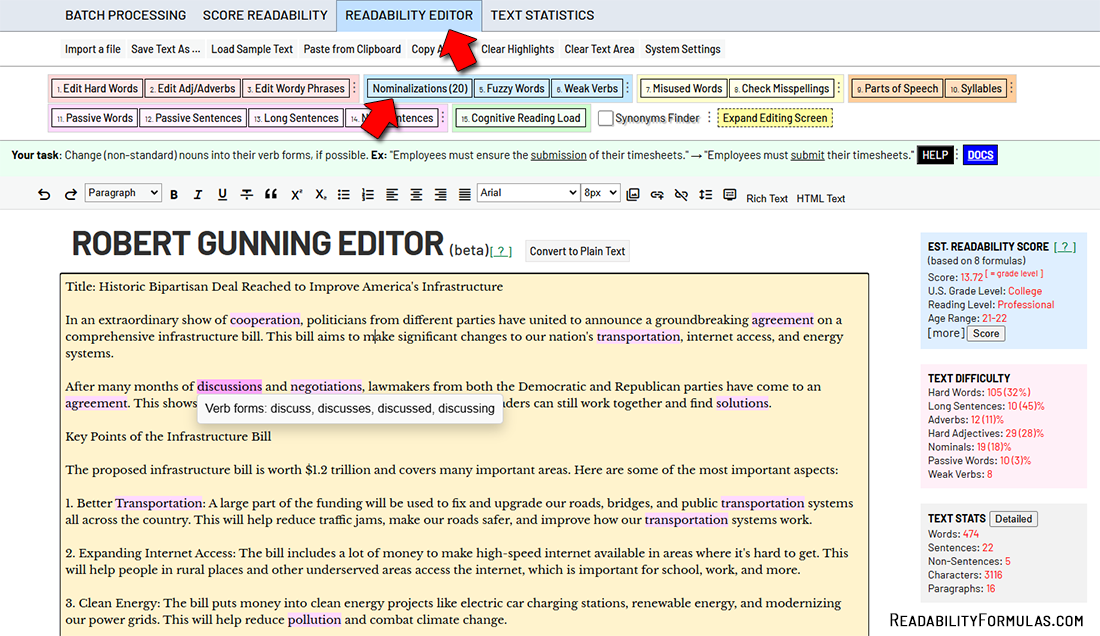

Find Nominalizations with the Robert Gunning Editor

Use the Robert Gunning Editor to highlight all nominalizations in your text. Simply go to our Readability Scoring System to start. Import your text, click on Readability Editor, then click on Nominalizations.

Scott, Brian. “Unlocking Readability: The Hidden Pitfalls of Nominalizations.” ReadabilityFormulas.com, 18 Feb. 2025, https://readabilityformulas.com/the-hidden-pitfalls-of-nominalizations/.