Syntactics refers to the study of sentence structure, word order, grammar, and word usage to convey meaning effectively and coherently. When writing for educated readers, ages 18-24, we can identify specific syntactics or patterns from a corpus of college-level texts that can help make our writing more readable. Don’t always assume educated readers can understand what you’re communicating. Using jargon, long-winded sentences, and big words can still hinder their reading experience.

Syntactics refers to the study of sentence structure, word order, grammar, and word usage to convey meaning effectively and coherently. When writing for educated readers, ages 18-24, we can identify specific syntactics or patterns from a corpus of college-level texts that can help make our writing more readable. Don’t always assume educated readers can understand what you’re communicating. Using jargon, long-winded sentences, and big words can still hinder their reading experience.

Syntactics includes several aspects:

- Sentence Structure: Syntactics involves understanding different sentence structures, such as simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences. Writers need to know how to construct these sentences to convey information accurately.

- Word Order: Word order plays a crucial role in conveying the intended meaning of a sentence. Writers need to understand how changing the order of words can alter the emphasis and clarity of a sentence.

- Punctuation: Proper use of punctuation marks, such as commas, semicolons, and dashes, affects the syntactic structure of sentences. Correct punctuation helps to avoid confusion and enhances readability.

- Parallelism: Parallel structure ensures that similar ideas are presented in a consistent manner, contributing to clarity and coherence. Writers use parallelism for lists, comparisons, and series of items.

- Active and Passive Voice: Know when to use active voice (subject performs the action) and passive voice (subject receives the action). Active voice is preferred in college-level material due to its directness and clarity.

- Modifiers: Knowing how to use adjectives and adverbs to modify nouns and verbs helps writers convey precise meanings and enhance their descriptions.

- Conjunctions and Transitions: Correct use of conjunctions (and, but, so) and transitional phrases helps writers connect ideas and create a logical flow between sentences and paragraphs.

- Subordination and Coordination: Writers use subordination (making one idea dependent on another) and coordination (joining two or more equal ideas) to create complex sentence structures that convey relationships between ideas.

- Sentence Length and Variety: Writers must consider the length and variety of sentences. A balance between short and long sentences engages readers and prevents monotony.

- Conciseness: Syntactic structures that convey ideas succinctly contribute to clear and effective writing. Eliminating unnecessary words and redundancies enhances readability.

- Discipline-Specific Conventions: Different academic disciplines have their own syntactic conventions and styles. Writers should acquaint themselves with these conventions to communicate effectively.

READING SPEED

Reading speed can vary widely among college-level readers due to individual habits, subject familiarity, and text complexity.

- Words Per Minute (WPM): on average 200 to 300 words per minute.

- Textbooks and Academic Materials (150 to 250 WPM): Reading speed for textbooks and academic materials is slower because of complexity, density of information, and the need for comprehension and retention.

- Novels and Fiction (200 to 300 WPM): When reading novels or fiction for leisure, college students read at a faster pace. The speed can vary based on engagement with the story and the familiarity with the author’s writing style.

- Research Articles and Journals (150 to 250 WPM): Reading research articles and academic journals requires careful attention to detail and comprehension of technical terminology.

- Online Articles and Web Content (250 to 350 WPM): College students skim and scan to quickly extract key information.

- Poetry and Literary Analysis: Reading poetry or engaging in literary analysis can lead to slower reading speeds to appreciate the nuances in language, imagery, and symbolism.

- Technical Manuals and Guides (150 to 250 WPM): Technical manuals or guides might lead to slower reading speeds as readers need to understand instructions and procedures.

AVERAGE WORD LENGTH

Longer words appear more frequently in academic and technical texts, while shorter words appear in more conversational and informal writing.

- Academic Texts and Research Papers: averages 6-8 characters per word. Long Words (9+ characters) appear in 10-15% of the text.

- Fiction and Novels: averages 4-6 characters/word. Long Words (9+ characters), 5-10% of text.

- Online Articles and Web Content: averages 5-7 characters/word. Long Words (9+ characters), 8-12% of text.

- Technical Manuals and Guides: averages 7-9 characters/word. Long Words (9+ characters), 12-18% of text.

- Conversational or Informal Writing: averages 4-6 characters/word. Long Words (9+ characters), 3-8% of text.

AVERAGE SENTENCE LENGTH

Varying sentence lengths can create a dynamic rhythm and engage educated readers.

- Academic Texts and Research Papers: averages 20-30 words/sentence. Long sentences (31+ words): 10-15% of text.

- Fiction and Novels: averages 15-25 words/sentence. Long Sentences (26+ words): 5-10% of text.

- Online Articles and Web Content: averages 12-20 words/sentence. Long sentences (21+ words): 8%-12% of text.

- Technical Manuals and Guides: averages 18-25 words/sentence. Long sentences (26+ words): 10-15% of text.

- Informal Writing: averages 10-20 words/sentence. Long sentences (21+ words): 3-8% of text.

SENTENCE STRUCTURES

College-level readers can navigate the flow of text that uses different sentence structures. The type of sentence can influence a text’s meaning, rhythm, tone, and clarity.

- Simple Sentences: Simple sentences, consisting of one independent clause, are common in college-level reading material. They provide clarity and straightforward communication. 30% to 40% of sentences.

- Compound Sentences: Compound sentences—which combine two or more independent clauses—are used to connect related ideas or contrast different viewpoints. 20% to 30% of sentences.

- Complex Sentences: Complex sentences, using one independent clause and at least one dependent clause, prevail in academic writing to provide depth and to convey relationships between ideas. 20% to 30% of sentences.

- Compound-Complex Sentences: These sentences combine compound and complex structures to express intricate relationships and nuanced ideas. 10% to 20% of sentences.

- Interrogative Sentences: Interrogative sentences—asking questions—engage readers and foster curiosity. 5% to 10% of sentences.

- Imperative Sentences: Imperative sentences—issuing commands or instructions—are found in college-level guides, manuals, and instructional texts. 5% to 10% of sentences.

- Exclamatory Sentences: Exclamatory sentences, expressing strong emotions, are used to convey excitement or emphasis. 1% to 5% of sentences.

VOCABULARY LEVELS

- Basic Vocabulary (2,000 to 5,000 words): College-level readers excel at basic vocabulary, which includes common words used in everyday communication and general reading.

- Intermediate Vocabulary (5,000 to 10,000 words): College-level readers use intermediate vocabulary— specific and nuanced words that contribute to a deeper understanding of texts.

- Advanced Vocabulary (10,000+ words): These educated readers learn advanced vocabulary relevant to their academic discipline and subject matter. This includes specialized terminology and technical jargon.

- Reading Proficiency: They can understand and interpret complex texts, even if they encounter unfamiliar words. They often use context clues and their language proficiency to derive meaning.

PASSIVE VS. ACTIVE VOICE

The use of passive and active voice can vary depending on the writing style, discipline, and purpose of the text.

- Active Voice: Active voice is preferred in college-level writing for its directness, clarity, and emphasis on the subject performing the action. Active voice may account for 60-80% of sentences in college-level materials.

- Passive Voice: Passive voice is used selectively to emphasize the action or the recipient of the action; it is more common in technical or scientific writing. Passive voice is 20-25% of sentences, but can be much higher, especially in lab reports or scientific papers.

- Passive Voice (Sciences): 20-40% | Prevalent in scientific writings, the passive voice is used to depersonalize observations and emphasize the action rather than the actor.

SYLLABLES

Given that college-level texts use more complex vocabulary, the average number of syllables per word is higher than in more casual texts. While general English averages 1.5 syllables per word, college-level texts average closer to 1.8 to 2.2 syllables per word.

- One-Syllable Words (monosyllabic): These are the most common, even in academic texts, due to the prevalence of function words (e.g., “a,” “the,” “is,” “of,” “to”) and many common nouns and verbs. 50-60% of the text.

- Two-Syllable Words (disyllabic): These become more common in academic writing as students learn domain-specific terminology. | 25-30% of the text.

- Three-Syllable Words (trisyllabic): These are more frequent in academic texts than in general prose. Terms like “university,” “literature,” and “functional” fall into this category. 10-15% of the text.

- Four or More Syllables (polysyllabic): Though less common than shorter words, these words frequently appear in academic texts than in casual reading materials. They often include technical terms, compound words, or words derived from Latin or Greek. Examples include “biodiversity,” “anthropological,” and “interpretation.” | 5-10% of the text.

These percentages will vary based on the topic, discipline, or even the author’s style. For example, a scientific paper on molecular biology would likely have a higher percentage of polysyllabic words compared to a college-level literary analysis.

LEXICAL DENSITY

When analyzing college-level texts for repeat words versus unique words, we are actually looking at the lexical density and lexical diversity.

Lexical density refers to the proportion of content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) to the total number of words in a text. Higher lexical density means a text has more content words and fewer function words (like prepositions, articles, and conjunctions). College-level texts have higher lexical density than spoken language because they are information-rich and use fewer redundant phrases.

Lexical diversity measures the variety of words in a text. It’s calculated by dividing the number of unique words (types) by the total number of words (tokens) in a text.

For example, in the sentence “The cat chased the mouse and the mouse ran away,” we count 9 total words but only 6 unique words. So, the type-token ratio is 6/9 or 0.67 (67%).

College-level texts often have a higher type-token ratio than spoken language or children’s texts because they draw from a broader vocabulary and introduce specialized terminology. However, longer texts might see a decrease in the ratio because writers have more opportunities to repeat words. Many academic texts have a ratio from 40-60% (unique words).

Lexical Cohesion: Synonyms, antonyms, and related words to maintain thematic consistency and coherence in a text. Present in approximately 30-40% of sentences.

AVERAGE PARAGRAPH LENGTH

- Short Paragraphs (1-3 sentences/10-15% of the text): These can be introductory or concluding paragraphs, or they are used to make a specific point or to introduce a new sub-topic. Short paragraphs consist of 50 words or fewer.

- Medium Paragraphs (4-6 sentences/40-50% of the text): These are common in academic writing and provide enough space to elaborate on a point, present evidence, and draw a conclusion. | 50-150 words/paragraph.

- Long Paragraphs (7+ sentences/35-45% of the text): College-level readers can navigate long paragraphs used in detailed discussions, lengthy analyses, or multiple examples. Long paragraphs appear in dense academic papers, especially in the humanities. | 150+ words/paragraph.

Factors Influencing Paragraph Length:

- Discipline: Sciences favor shorter, more concise paragraphs, while humanities have longer, more exploratory paragraphs.

- Purpose: An abstract or summary will have shorter paragraphs compared to the main body of a paper.

- Audience: Texts for broader academic audiences or introductory courses might use shorter paragraphs for clarity and accessibility, while specialized journals might have longer, denser paragraphs.

PUNCTUATION

- Periods (.): 30-40% | Since they mark the end of most sentences, they’re the most common punctuation mark.

- Commas (,): 40-50% | Given their varied uses, commas might surpass periods in terms of frequency in college-level texts, especially those with complex sentence structures.

- Semicolons (;): 1-3% | They’re less frequent and used for specific purposes, like connecting related independent clauses.

- Colons (:): 2-4%. Used to introduce lists, explanations, or quotations.

- Question Marks (?): 0.5-2% | Direct or rhetorical questions might be rare.

- Exclamation Points (!): <1% | Quite rare in formal academic writing.

- Quotation Marks (“ ” or ‘ ’): 5-10%.| Quotations might be frequent or rare.

- Parentheses (): 3-5% | Used for supplementary info or in-text citations in certain citation styles.

- Brackets []: <1% | Mostly seen within quotations for clarity or corrections.

- Dashes (—): 1-3% | Used for emphasis or parenthetical statements.

- Ellipsis (…): <1% | Rarely seen in formal academic texts.

- Hyphens (-): 2-4% | Used for compound words or adjectives.

- Apostrophes (’): 2-5%. Indicating possession or, less commonly in academic writing, contractions.

ABBREVIATIONS

In college-level texts, abbreviated words can be prevalent based on the discipline, writing conventions, and the nature of the document.

- Common Abbreviations: 2-5% | Words like “etc.” (et cetera), “e.g.” (for example), “i.e.” (that is), and “vs.” (versus) are common.

- Academic Degrees and Titles: Abbreviations like “Ph.D.,” “M.A.,” “B.Sc.,” and “Dr.” are common, especially in biographical contexts or formal acknowledgments. In a biographical context or academic profiles, the percentage is higher (5-10%), while in most texts, it is less than 1%.

- Units of Measurement: 10-20% | In scientific papers, units like “km” (kilometers), “mg” (milligrams), “s” (seconds), and others are standard.

- Scientific and Technical Abbreviations: 5-15% | Fields like biology, medicine, and engineering use specific abbreviations like “DNA,” “MRI,” or “LED.”

- Organizations and Institutions: 3-10% | Organizations like the “WHO” (World Health Organization) or “NASA” are abbreviated after the first mention.

- Latin Abbreviations: “et al.” (and others), “cf.” (compare), “ibid.” (in the same place) are used, especially in referencing. In heavily referenced texts or literature reviews, these can make up 2-8% of the text.

- Field-Specific Abbreviations: 5-10% | Various academic fields have their unique abbreviations. For example, linguistics might use “IPA” for International Phonetic Alphabet, while computer science might use “AI” for artificial intelligence.

PROPER NOUNS

Proper nouns are specific names that identify unique entities, such as individuals, places, institutions, titles of works, and more.

- Research and Citations: 5-15% of the text | In academic research papers, proper nouns appear frequently in citations. The names of authors, journals, institutions, and sometimes locations can pepper a document.

- History and Humanities Texts: 10-20% | Texts related to history, literature, and the humanities will often contain names of historical figures, places, events, and works of art.

- Scientific Papers: 2-8% | In the sciences, proper nouns appear less frequently and may be associated with named processes, researchers, institutions, or specific locations related to the study.

- Business and Economics: 5-10% | Texts in these fields might contain names of companies, financial institutions, economic policies, and prominent figures in the industry.

- Textbooks: 3-10% | While textbooks introduce and explain concepts, they will often reference historical figures, foundational works, institutions, or unique terminologies.

- Fiction and Literary Analysis: Literary works used in college courses, or analyses of such works, will contain character names, locations, titles of works, and sometimes authors. In works of fiction, proper nouns (like character and place names) make up 5-15% of the text. In literary analyses, this is lower, around 3-10%, depending on the depth of the discussion.

- Field-Specific Proper Nouns: Varies widely | Different disciplines have unique entities, terminologies, or names specific to their field. A paper discussing the “Freudian” approach will mention “Sigmund Freud” more than one discussing general psychology, for instance.

NUMBERS

Numbers (both written out and in numerical form) are found in college-level texts, but their prevalence varies based on the type of material and the discipline.

- Science and Engineering: Papers in these disciplines include data, statistics, measurements, quantities, and formulas. | 5-20% of the content, especially in tables, charts, and formulae.

- Economics and Business: 5-15% of the text | These areas discuss financial figures, percentages, statistics, and other quantitative measures.

- History and Humanities: 2-5% | While history does discuss dates, events, and statistics, it is less number-focused than disciplines like science or economics.

- Mathematics: 10-25% | Mathematics papers and textbooks will contain many numbers, along with symbols and equations.

- Social Sciences: 5-10% | Papers in disciplines like psychology, sociology, and anthropology contain statistics, survey results, and measurements.

- Literature and Language Studies: <2% | Numbers appear less frequently in these fields unless the discussion revolves around historical contexts, editions of books, or other quantifiable aspects.

- General Textbooks or Overviews: 2-5% | Introductory or general knowledge textbooks across disciplines contain fewer numbers.

- Reference and Footnotes: Numbers used for citations, page numbers, and referencing can add to the count, especially in heavily cited papers or texts.

PARTS OF SPEECH

Here’s a breakdown of parts of speech and their potential prevalence in college-level texts:

- Nouns: Nouns are a dominant part, emphasizing specific concepts, objects, people, and places. | 25-30% of the text.

- Verbs: Verbs are common. | 15-20% of the text.

- Adjectives: Adjectives are used to qualify nouns, and their usage is higher in humanities texts compared to scientific papers. | 10-15% of the text.

- Adverbs: They modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. They are used less in more casual prose. | 5-10% of the text.

- Pronouns: First-person pronouns are less common in formal academic papers, but they are more prevalent in opinion pieces or humanities essays. 5-8% of the text.

- Prepositions: Prepositions are vital for establishing relationships between nouns and other words. | 10-15%

- Conjunctions: These link words, phrases, or clauses. Conjunctions help maintain flow and coherence. | 5-10% of the text.

- Articles (Definite & Indefinite): Articles (“the,” “a,” “an”) are common in English. | 8-10% of the text.

- Interjections: Interjections are rare. <1% of the text.

- Modal Verbs: These are auxiliary verbs (e.g., “can,” “will,” “should”) that express necessity, possibility, permission, or ability. 2-5% of the text.

- Nominalizations: College-level texts often turn actions into concepts by using nouns derived from verbs (e.g., “demonstration” from “demonstrate”). | 10-20% more than in casual writing.

- Modals: Modal verbs express degrees of possibility, necessity, or certainty. Depending on the nature of the discussion (e.g., speculative vs. definitive), modal verbs appear in 15-30% of sentences.

- Coordination and Subordination: Coordinating conjunctions (and, but, or, nor, for, so, yet) and subordinating conjunctions (although, because, since, unless) are common to create compound and complex sentences respectively. Varies, but expect 30-40% of sentences.

WRITING FOR EDUCATED READERS

Here’s how you can tell if college-level readers might find your writing too challenging:

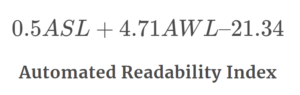

Check Readability: Use tools like Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Gunning Fog Score, and SMOG index. These tools evaluate sentence length and word complexity, resulting in a grade level.

Sentence Length: Complex sentences are common in academic writing but can hinder clarity if overused. Break down lengthy sentences if needed.

Avoid Excessive Jargon: Overloading text with technical terms can alienate readers unfamiliar with the subject. Use specialized terms only when necessary and provide explanations.

Smooth Transitions: Sudden topic shifts can confuse readers. Ensure a logical flow between ideas.

Simplify Complex Ideas: College readers grasp intricate concepts, but clear explanations with context are key. Avoid assumptions about reader knowledge.

Question Assumptions: Don’t presume your audience shares your knowledge. Even within college, backgrounds vary.

Benchmark Against College Texts: Compare your writing to standard texts in similar courses for a target reading level.

Use Analogies and Examples: Concrete analogies and real-world examples help clarify abstract ideas. If still challenging, your content might be overly intricate.

Prioritize Clarity: While eloquent prose is nice, prioritize clear communication, especially for complex ideas.

In summary, college-level readers can handle complexity, but clarity is paramount. Regular feedback, readability tools, and self-review are vital to ensure your writing resonates effectively.