Mrs. Elaine Harper, a retired English teacher, recently hosted a writer’s workshop at her local library in Tulsa, OK. Among the attendees were Jack, a young novelist with a penchant for elaborate prose; Lily, a technical writer who loved her jargon; and Ethan, a poet known for his rich, metaphorical language. Each of them had a unique style, but they all struggled with making their writing accessible to a broader audience.

As the workshop began, Mrs. Harper introduced the concept of Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) and its relevance to writing. “Think of your reader’s mind like a sky,” she began. “Your words are the clouds in this sky. Too many clouds, or clouds that are too dense, and your reader can’t see the clear blue behind them. Our job as writers is to balance these clouds–to convey our messages without clouding our reader’s understanding.”

The first exercise was simple. Mrs. Harper asked each attendee to write a brief description of the same object: a small, antique clock that sat on the library’s mantle. Jack wrote a paragraph rich with imagery and flowery language; Lily’s description read like a technical manual, precise but peppered with technical terms; Ethan’s version was a poetic ode to time, abstract and metaphorical.

Mrs. Harper read each description aloud. “Notice how each of you has approached this differently,” she said. “Jack, your description is beautiful, but it’s overwhelming with detail. Lily, your precision is admirable, but it’s not friendly to a non-technical reader. And Ethan, while your metaphors are stunning, they obscure the simple beauty of the clock.”

She then introduced them to the principles of plain English, a popular writing style that reduces cognitive load on readers: use simple words, be concise, prefer active voice, avoid jargon, and keep your audience in mind. “Let’s rewrite these descriptions.” she proposed, “And keep these principles at the forefront.”

The trio set to work, revising their descriptions. Jack trimmed his elaborate adjectives in favor of stronger verbs; he focused on clear, vivid imagery. Lily replaced technical terms with everyday language, making her description more conversational. Ethan distilled his metaphors, preserving the beauty while ensuring clarity.

When they read their revised descriptions, the change was palpable. Each piece retained its unique voice but was now clearer, like a sky after a storm, with just enough clouds to beautify the view without obscuring it.

Why Cognitive Load Matters in Everything You Write

John Sweller developed Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) in the 1980s. He revealed how the human brain processes new information and stores it in long-term memory. The main idea is that our working memory has limited capacity at any given time. If you reduce cognitive load on readers, you increase their ability to understand, retain, and act on your information.

Three cognitive loads affect your readers:

- Intrinsic Cognitive Load: the complexity of your content. Do your readers find your topic too challenging or too easy to understand?

- Extraneous Cognitive Load: the way you present the information. Do you organize your text to reduce complexity? Do you help readers understand and remember your message?

- Germane Cognitive Load: the mental effort readers use to process, construct, and automate what they’ve read. Do you help readers connect their own experiences with your topic?

A single sentence can trigger multiple instances of cognitive load on a reader. Take, for instance, the following sentence:

"Ensure the device is turned off and disconnected from the power source before doing any maintenance."

To process and remember this sentence, readers go through these steps:

Step 1: Word Recognition: They identify and understand words like “ensure,” “disconnected,” and “maintenance.”

Step 2: Syntax: They decipher the sentence structure, which is a simple imperative sentence with a conditional clause.

Step 3: Phrase Recognition: They break down the sentence into key phrases: “ensure the device is turned off,” “disconnected from the power source,” “before doing any maintenance.”

Step 4: Contextual Meaning: They reshape the meaning of the sentence in the context of safety during maintenance.

Step 5: Actions: They identify the main action (turning off and disconnecting the device) and the condition (before maintenance).

Step 6: Logical Order: They learn the sequence of actions for safety purposes.

Step 7: Knowledge: They try to relate the instructions to general knowledge about electrical safety and device maintenance.

Step 8: Inferencing: They infer the importance of safety to prevent accidents or damage to the device.

Step 9: Mental Images: They visualize the action of turning off the device and unplugging it from the power source.

Step 10: Memory Encoding: They try to remember the essential safety steps multiple times: “Turn off and unplug the device before maintenance.”

Step 11: Rehearsing: They mentally or physically rehearse the action as described for better retention and understanding.

These steps show how a simple sentence from a user manual can trigger cognitive load, forcing readers to decode, comprehend, and memorize what they’ve read. That sentence had only 16 words, but it triggered 11+ instances of cognitive load. What about the last email you read. Were you able to scan a few sentences to know its meaning? Or did you need time to process it and figure out how to reply to it?

Knowing how cognitive load affects readers can help you write more accessible content to a broader audience. Let’s find out how these writers did it.

Scenario #1: Writing an Article on Quantum Computing

- Intrinsic Cognitive Load: Quantum computing is inherently complex to understand. To manage the intrinsic load, Matt Redding, a journalist for a mainstream science magazine, breaks down the concept into simpler elements. He starts with the basics of regular computing and then introduces quantum concepts, step-by-step. He presents foundational ideas clearly before diving into more challenging topics.

- Extraneous Cognitive Load: To reduce extraneous load, Matt uses a clear and concise writing style. He avoids jargon and uses everyday language to explain complex concepts. The article is well-structured with subheadings, bullet points, and diagrams to visually convey ideas. This organized format helps readers follow along without slowing them down.

- Germane Cognitive Load: To enhance germane load, Matt encourages readers to relate new information to what they already know. For example, he helps readers compare a quantum bit (qubit) to a traditional binary—but it can exist in multiple states simultaneously. He highlights industries that use quantum computing, like in cryptography or cloud storage. He gradually helps readers understand the applications of the concept.

Scenario #2: Writing a Blog Post on Healthy Eating Habits

- Intrinsic Cognitive Load: Healthy eating can be a broad and complex topic. Sandy James, a nutritionist with a Ph.D. in translational health, simplifies the topic by focusing on everyday themes like balanced nutrition, portion control, and hydration. She introduces these concepts one at a time, so as not to overwhelm readers with too much information.

- Extraneous Cognitive Load: To minimize extraneous load, Sandy uses a friendly and conversational tone. She includes real-life examples and easy-to-follow tips; she makes the content relatable and easy to digest. She organizes the blog post with clear headings, bullet points, and text call-outs. Simple infographics summarize key points, such as a plate showing portion sizes.

- Germane Cognitive Load: Sandy enhances germane load by linking the information to readers’ daily lives. She suggests simple changes to regular meals to make them healthier. She offer tips on how to introduce more fruits and vegetables into one’s diet. She offers actionable steps and encourages readers to reflect on their current eating habits.

Scenario #3: Writing a User Manual for a New Smartphone

- Intrinsic Cognitive Load: Smartphones are complex devices with numerous features. Ben Dedrick, a tech writer for a mobile phone maker, is in charge of writing how-to manuals for everyday users. He categorizes the manual into sections like “Getting Started”, “Basic Functions”, “Advanced Features”, etc. He introduces basic functions before explaining more complex features. He creates a gradual learning curve.

- Extraneous Cognitive Load: To keep extraneous load low, Ben uses simple language, devoid of technical jargon. He uses step-by-step instructions with images for each action. The layout is clean, with plenty of white space. He uses icons to highlight important points like safety warnings or tips.

- Germane Cognitive Load: Ben helps readers form relevant mental models with real-world scenarios where users might use certain features. For instance, Ben explains the benefits of a specific camera mode in certain lighting conditions; or how to use voice commands when hands are occupied. He relates features to everyday situations to embed this knowledge in the readers’ long-term memory.

How Syntax Affects Cognitive Load

Writers can further reduce cognitive load on readers by analyzing their text’s syntax—the rules that govern sentence structure. The following syntactics affect cognitive load.

Sentence Length: Longer sentences can increase cognitive load. Keep sentences around 15-20 words. This range is ideal to convey a complete thought or idea without overwhelming the reader.

Sentence Structure: Frequent use of complex or compound-complex sentences can increase cognitive load.

Syntax Complexity: Count the number of clauses per sentence. A higher number of clauses, especially subordinate clauses, can affect complexity. Look for nested structures, as these can be more difficult to process.

Passive Voice: Identify passive voice. Passive voice can be less direct and harder to process than active voice, thus increasing cognitive load. Passive voice should be less than 10% of your text.

Negations and Conditionals: Count the number of negations and conditional phrases. These can add complexity to sentences and meaning.

Parallelism: Check for consistency in parallel structures. Lack of parallelism can make lists or comparisons harder to follow.

Syntactic Ambiguity: Identify syntactic ambiguity that make sentences harder to interpret.

Word length: Longer words, especially those less common or more complex, can increase cognitive load. They require more mental effort to decode and understand, especially for low-level readers or readers unfamiliar with the subject. Texts for a general audience use words averaging 4-5 letters.

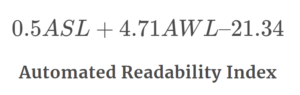

How to Measure the Cognitive Load of a Text

You can use different ways to measure cognitive load of a text, from user testing to online surveys and feedback. But the easiest and quickest way is with readability formulas—tools to assess the complexity of a text. Tools like the Flesch-Kincaid Readability Test, Gunning Fog Index, or the SMOG Index will evaluate the complexity of your text and output a score that aligns with a grade level or reading scale. A text with a high readability score (indicating it’s easier to read) imposes a lower cognitive load on the reader. This means the reader can understand and absorb the material more efficiently without becoming overwhelmed or fatigued. While these formulas don’t measure cognitive load directly, they offer a proxy by indicating how challenging the text might be for the average reader.

Scenario #1: Creating Educational Materials for Middle School Students

Julia McCall, an educational content developer, is contracted to create a science textbook for middle school students. She needs to convey complex scientific concepts that 12-14-year-olds will find engaging and easy to understand. She plans to use a readability formula to estimate the cognitive load that her information will place on readers.

Initial Assessment:

Julia drafts a chapter on basic principles of ecology. Her initial draft is fairly technical; she uses terms and sentences that she finds easy as a science expert.

Readability Score Analysis:

She uses a readability formula to evaluate her draft. The formula outputs a number that matches a U.S. grade level. The score indicates the text is at a 10th-grade reading level, which is higher than the target audience’s level (middle school).

Adjusting for Cognitive Load:

She knows a high reading level will impose too much cognitive load on middle schoolers as they try to decode and retain scientific concepts. She begins to revise, rescoring her text along the way. She simplifies sentences, breaks down complex paragraphs, and replaces jargon with common terms. She uses simple diagrams, Q&As, infographics, and visual cues to help students learn new words and theories. These changes make the text easier to process, thus reducing cognitive load.

Re-evaluating Readability:

Her last revision aligns with a 7th-grade reading level. She knows this is appropriate for these students.

Feedback and Further Adjustments:

To ensure the cognitive load is balanced, she tests her material with a group of middle school students. She observes their reading process, asks questions to gauge their understanding, and collects feedback on the text’s clarity and readability.

Final Outcome:

The feedback confirms the first chapter is accessible and understandable. Students can engage with the material without feeling overwhelmed—a successful balance of readability and cognitive load.

Understanding Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) reveals that every piece of writing—an article, a blog post, or a user manual—can affect readers in different ways. By breaking down the intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive loads, you can tailor content that helps readers comprehend and retain information.