In a small, sunlit classroom, Ms. Thompson observed her diverse group of students. Among them was Julia, a bright girl with dyslexia, often frustrated by jumbled letters. Next to her sat Leo, whose keen mind was hindered by his partial blindness, making standard texts appear as faint whispers of ink.

On a typical day, reading sessions were challenging. Julia’s dyslexia turned simple paragraphs into puzzles, while Leo’s vision needed large texts, losing context on each oversized page. However, this day was different.

Ms. Thompson introduced a new digital reading platform. The software featured text-to-speech for Leo—it allowed him to hear the stories he longed to see. The software had dyslexia-friendly fonts for Julia—it turned her chaotic alphabetic swirls into a stress-free readable flow. As Leo listened to the narrated text, his face lit up with excitement. Meanwhile, Julia discovered a newfound fluency as she could see words with clarity. Leo could now debate the finer points of the story. Julia, once hesitant, could now read with confidence.

This moment, simple yet groundbreaking, highlights the power of readability in our digital age. Thoughtful design and technology can bridge the gap between accessibility and aspiration, turning challenged reading into a universal pleasure. Elevate readability, and communication thrives for everyone, regardless of visual or cognitive impairments.

Impairments in Reading Text

Even with readability in mind, text may impair readers to understand. Let’s look at the most common impairments that challenge readers:

1. Visual Impairments: Including blindness, low vision, and color blindness. They may rely on Braille or screen readers to access written content. Not all visual impairments result in total blindness. Conditions like macular degeneration or glaucoma may reduce vision but not eliminate it. For such individuals, larger text, high contrast, and certain font styles can help. Color perception varies also. Using color alone to convey information might confuse these readers. You can use patterns or text labels alongside colors.

The CDC has estimated that the population of adults with vision impairment and age-related eye diseases is expected to double in the next three decades, influenced by the aging U.S. population and the diabetes epidemic.

2. Cognitive and Learning Impairments: Such as dyslexia, dysgraphia, hyperlexia, and attention deficit disorders. Dyslexia affects the brain’s ability to process language. Dyslexic readers might jumble letters or confuse word meanings, impacting fluency and comprehension. Dyslexia affects about 10% of the population, according to the International Dyslexia Association.

3. Language and Linguistic Impairments: Challenges faced by non-native language speakers or readers with expressive and receptive language disorders. Reading in a second (or third) language can pose challenges, even if the person is fluent. Idioms, cultural references, or certain sentence structures might confuse these readers.

Expressive and receptive language disorders affect an estimated 7-8% of children in the United States” (Source: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association).

4. Neurological Disorders: Conditions like Autism Spectrum Disorder or seizure disorders might affect reading. Some readers might struggle with figurative language, while others excel at reading but find it hard to process emotional nuances. For those with photosensitive epilepsy, flashing animations or specific color patterns could trigger seizures.

Around 1 in 4,000 individuals have photosensitive epilepsy, making certain visual stimuli a significant concern in reading materials (Source: Epilepsy Foundation)

5. Motor Impairments: Conditions such as dyspraxia (a neurological disorder that affects motor skill development) might indirectly impact the cognitive processes behind reading; these readers may find it difficult to navigate traditional and digital reading platforms. Turning pages, using a mouse, or scrolling can be troublesome.

Approximately 1 in 10 people worldwide live with a disability, and many of them face challenges in accessing and navigating digital reading platforms. (Source: World Bank)

6. Emotional and Psychological Factors: Including reading anxiety or trauma-related triggers. Past failures or struggles with reading can create anxiety, making the individual apprehensive about reading. Certain topics or styles of writing might trigger traumatic memories or responses, causing them to disengage or overwhelm them.

An estimated 2.2 billion people globally have a vision impairment or blindness (World Health Organization, 2019). Among internet users, approximately 12% use some screen enhancement tools, including magnifiers or screen readers.

How to Help Impaired Readers

Making content easy to read for impaired readers is more than writing in plain English or relying on readability scores. It’s about making sure everyone—no matter their abilities—can understand the information. Here’s how.

1. Visual Impairments:

- Use of Alt Text: All images, graphs, and visual media should include alternative text descriptions. This provides context for screen readers, allowing users to understand the content’s intent. Example: A product image on an e-commerce website has an alt text: “Blue women’s rain jacket with hood.”

- High Contrast Modes: Using options for high contrast themes can aid readers with low vision. The contrast between background and foreground elements, like text, should be clear and distinct. Suggestion: A website offers a theme with black text on a white background and another with white text on a black background.

- Resizable Text: Allow users to resize text without loss of content or functionality. Avoid fixed font sizes; instead, use relative units. Example: A news website allows readers to adjust the text size using a sliding scale.

- Keyboard Navigation: Ensure users can access all functions of a webpage using only the keyboard. This will help readers who can’t use a mouse due to visual or motor impairments. Example: On a blog, readers can use the ‘Tab’ key to jump between articles without using a mouse.

Over 70% of students with learning disabilities in the U.S. spend 80% or more of their school day in general education classrooms, emphasizing the importance of universally designed educational content.

2. Catering to Cognitive and Learning Impairments:

- Simple Language: Use clear, concise language and avoid jargon. Breaking down complex ideas into simpler terms benefits readers. Example: Instead of writing “acquire,” use “get”; instead of “utilizing”, replace with “use.”

- Structured Content: Use headers, sub-headers, bullet points, and numbered lists to break up content. This adds visual breaks and organizes information. Example: An online recipe uses headers and bullet points for ingredients, preparation, cooking method, and serving suggestions.

- Consistent Layouts: Keep the layout consistent across pages or sections. A familiar layout will simplify navigation, especially for readers with cognitive challenges.

- Multimodal Presentation: Offer information in multiple formats—text, audio, video, and graphics—to cater to different learning styles and preferences. Example: A how-to article on planting a tree is accompanied by an instructional video and an infographic.

3. Language and Linguistic Impairments:

- Translation and Localization: A global audience will appreciate translated versions of your content. This aids non-native speakers and ensures clarity across linguistic barriers. Example: A tech gadget’s manual is available in English, Spanish, Chinese, and French.

- Glossaries and Definitions: If you use specialized terms or jargons, add a glossary or inline definitions. Example: A scientific article about space provides a glossary explaining terms like “blackhole” or “nebula.”

- Contextual Clues: Using images, diagrams, or other visual aids can contextualize complex topics, aiding comprehension. Example: A textbook uses a side image of a cell next to the description of cell structure.

4. Designing for Neurological Disorders:

- Flashing or Blinking Content: To prevent seizure triggers for those with photosensitive conditions, avoid rapidly flashing or blinking elements. Example: A website advertising a Black Friday sale uses a static banner instead of a flashing one.

- Clear Navigation: Ensure that navigation menus are intuitive for users with cognitive impairments stemming from neurological conditions. Example: An e-learning platform has a sidebar that clearly labels modules, lessons, and quizzes.

- Emotional Nuance: Be mindful of the emotional weight of content, particularly for autistic readers who might interpret emotions differently. Example: A children’s story app for autistic kids explains that a character is “very happy” rather than relying on an ambiguous illustration.

Dyslexia affects approximately 5-10% of the world’s population, translating to potentially 780 million individuals who might experience challenges with traditional text.

5. Aiding Motor Impairments:

- Voice Commands: Add voice command prompts to help navigate and access content without relying on fine motor skills. Example: A smart home device lets users control lights, temperature, and music through voice.

- Touchable Targets: For touchscreen devices, ensure that users can tap spacious touch-targets (like buttons) without error. Example: A mobile banking app has large icons and buttons to ensure error-free tapping.

- Customizable Interfaces: Allow users to customize interface elements, such as button sizes or spacing. Example: A reading app lets users adjust button sizes based on their vision impairment.

Websites that adhere to accessibility guidelines see an average 30% increase in user engagement, leading to potential revenue increases.

6. Emotional and Psychological Factors:

- Content Warnings: If discussing potentially triggering topics, provide content warnings. This allows readers to prepare themselves or choose to skip that section. Example: A podcast episode about war includes a warning about graphic descriptions at the beginning.

- Feedback Channels: Allow users to provide feedback on content accessibility. This can offer insights into areas of improvement. Example: An online course has a feedback form at the end of each module asking about user experience.

- Positive Reinforcement: Especially on educational platforms, positive feedback mechanisms can reduce reading anxiety and encourage continued learning. Example: An e-learning platform gives digital badges for course completion.

High contrast text increases reading comprehension and speed by up to 40% for users with visual impairments.

7. General Best Practices:

- Accessibility Testing: Regularly test content with various assistive technologies (like screen readers) to ensure compatibility. Example: Before launching a new website, test it using JAWS (a popular screen reader) to ensure compatibility.

- Continuous Education: Stay updated with the latest in accessibility guidelines and standards. Suggestion: Web developers can attend a workshop on the newest Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) updates.

- Engage the Community: Engage with the differently-abled community and get their insights. Real-life feedback can provide valuable insights into accessibility challenges and solutions. Example: A software company holds focus groups with differently-abled users to understand their challenges with the product.

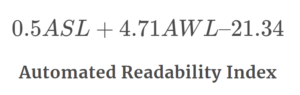

- Using Readability Formulas: Readability formulas can help you create clear, concise, and age-appropriate text for impaired readers. Content that scores lower means text is usually more accessible and readable. Example: a text with a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 5 will appeal to a broader audience than one with a grade level of 12. Shoot for a score around 8—the average readability of most people.