IMAGINE a high school student, Joseph, who loves to read. Joseph ventures into the school library one afternoon, eager for a new book. After some browsing, Joseph selects a thick novel that looks exciting. However, once Joseph starts reading, frustration sets in. The sentences are long and complex, the vocabulary unfamiliar. It’s not that Joseph can’t read, but this book seems like it’s written for someone much older.

This experience is common. It highlights a crucial aspect of reading: not all texts are equally accessible to all readers. This is where readability formulas come in. These tools, often unnoticed and underappreciated, work behind the scenes to help educators, publishers, and even libraries like the one Joseph visited, to categorize and recommend texts that match a reader’s comprehension level. Yet, despite their widespread use, many of us, like Alex, are unaware of the intricate science that determines why some books are easier to read than others.

A study by Scholastic shows that 91% of children (aged 6-17) say their favorite books are the ones they’ve picked out themselves, highlighting the importance of having accessible books at the right level.

Readability formulas have long been used as tools to: 1) score the complexity of written texts and 2) estimate the level of comprehension needed to understand them. These formulas measure the ease with which individuals can understand what they read. Despite their widespread use and renewed interest in the digital world, many users don’t know the subtle principles of these formulas.

It’s time to cast light on the science behind their scores, explore their limits, and suggest other methods for evaluating text readability.

Understanding Readability Formulas

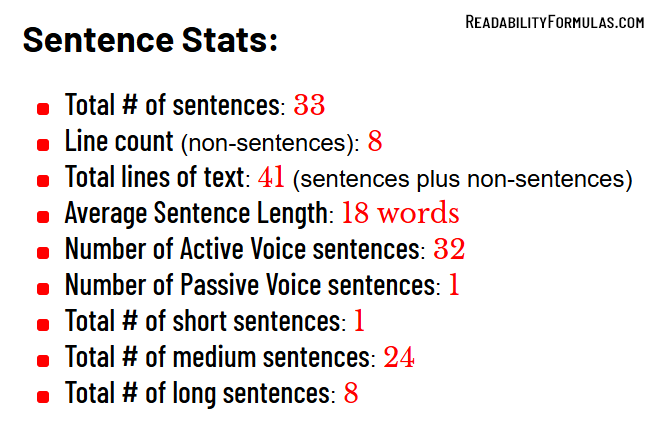

Readability formulas are algorithms that analyze various linguistics of a text to estimate its reading difficulty. They consider word length, sentence length, and grammatical complexity. The output is usually a grade level or reading scale, indicating the text’s reading ease or difficulty.

Research shows that 80% of readers understand texts written at or below the intended grade level.

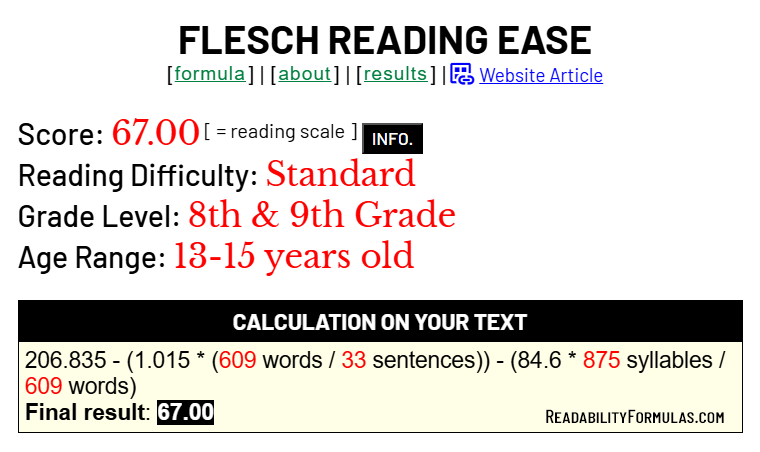

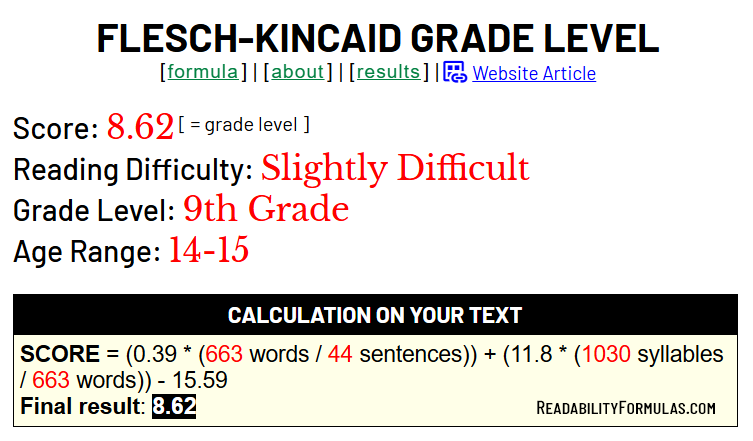

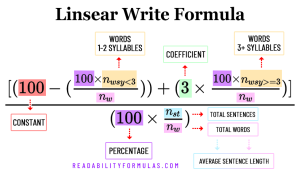

Popular formulas include the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Gunning Fog Index, Coleman-Liau Index, and SMOG Index. Each formula calculates differently to determine the readability level. For instance, the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level relies on average syllables per word and average number of words per sentence to estimate the grade level.

The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level is one of the most widely-used readability formulas. It’s also used in various software platforms, including Microsoft Word.

If you’re not a linguist with a Ph.D. or a scientist for NASA, a readability formula looks perplexing:

The Science Behind Readability Scores

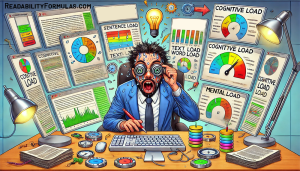

Readability formulas are rooted in linguistic and cognitive research. They draw on principles such as lexical complexity, syntax, and working memory/cognitive load to estimate a text’s difficulty. Some key factors include:

1. Word Length: Longer words are generally more challenging to comprehend than shorter words. These formulas score the average number of syllables or characters per word to assess difficulty. The Flesch Reading Ease is one such formula that analyzes words and syllables.

2. Syntax Complexity: Readability formulas analyze sentence variety within a text. Percentages of different sentence structures affect readability scores.

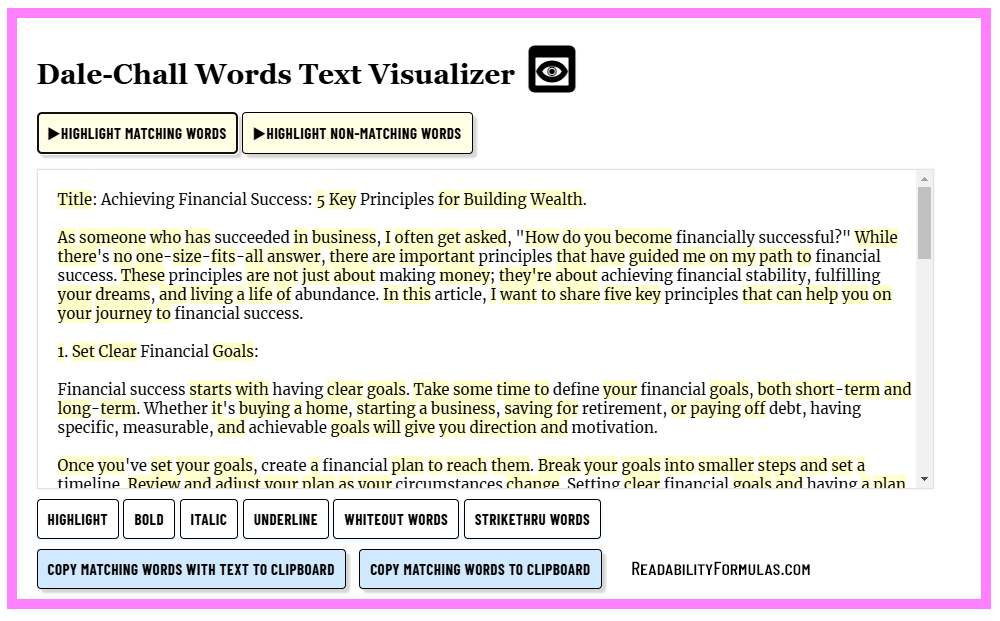

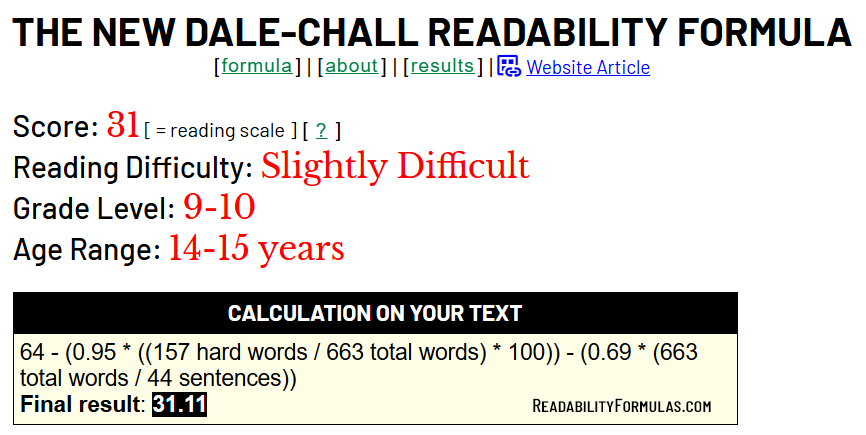

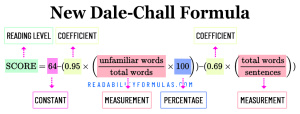

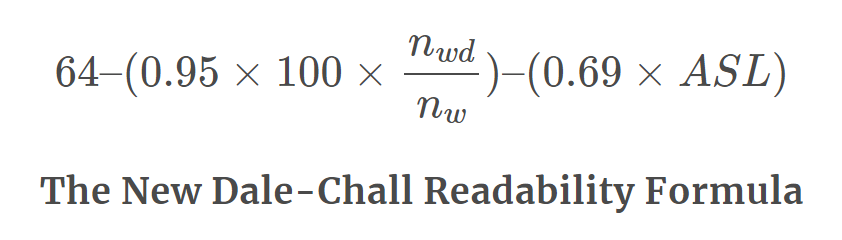

3. Vocabulary: The range of familiar words influence readability. These formulas often analyze unique words, repeat words, and unfamiliar words to estimate difficulty. Dale-Chall Formula is one such tool that analyzes familiar and difficult words.

4. Sentence Length: Longer sentences are more complex and need more working memory to reassemble and process. These formulas analyze the average number of words per sentence to gauge the text’s readability.

Studies show that up to 60% of U.S. corporations have used readability formulas to evaluate their customer-facing communications.

Grade Levels vs. Reading Scales

Readability scores correlate with one or two distinct yet related metrics: grade level scores and reading scales. Both metrics evaluate the readability of a text and can determine how easily and quickly a specific audience can read and understand the text.

Grade Level Scores: These scores align with U.S. school grade levels. For example, a score of 8 indicates the text is suitable for an 8th-grade student. The main emphasis is matching grade-level texts with students across different educational levels. The Flesch-Kincaid formula is one such formula that outputs a U.S. grade level.

Readability Scales: These scales concentrate on general readability for diverse audiences, including adults. They are used in various contexts, such as assessing the readability of legal documents, health information, and websites. The (new) Dale-Chall Formula uses a reading scale based on the ease or difficulty of reading.

Grade level scores are more tailored to educational contexts, while reading scales offer a broader assessment of text difficulty for a wider range of audiences.

Grade Levels / Reading Scales Comparison

| Grade Levels | Reading Scales | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Estimate the U.S. school grade level needed for comprehension. | Evaluate the ease of reading for general audiences. |

| Examples | Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Gunning Fog Index, SMOG Index | Flesch Reading Ease, Dale-Chall Readability Formula |

| Calculation Basis | Syllable count, word length, and sentence length. | Sentence length and a list of familiar or easy words. |

| Output Format | Number corresponds to a U.S. school grade level. | Numerical score on a scale (e.g., 0-100 for Flesch Reading Ease). |

| Use Case | Creating educational content, assessing textbook readability. | General content for public reading, such as news articles or product manuals. |

| Advantages | Directly relates to school curriculum levels; good for academic materials. | Provides a broad assessment of readability for diverse audiences. |

| Disadvantages | May not accurately reflect reading levels in non-academic populations or non-U.S. education systems. | General scale may not be specific enough for educational content; less effective with technical or highly specialized texts. |

Limits of Readability Formulas

While readability formulas can score text complexity quickly and conveniently, they have limitations:

1. Syntax Over Semantics: These formulas rely on general linguistics and ignore factors such as content relevance, cultural background, or prior knowledge of the reader.

2. Subjectivity: Different formulas may output different results for the same text. The subjectivity of readability scores calls into question their consistency and reliability.

3. Structure and Context: These formulas overlook how headings, subheadings, or layout influence comprehension. According to Reading Association, “78% of readers find texts with clear headings and bullet points more readable.”

4. Diversity: Readability formulas were designed for native English speakers and may not accurately score texts for non-native speakers or individuals with learning disabilities.

5. Jargon: These formulas treat all types of text as equal. They may count specialized vocabulary or industry-jargon as complex words, even though readers find them very familiar.

6. Writing Style: Some formulas focus on surface-level features and ignore the nuances of writing style. Tone, voice, and rhetorical devices can significantly impact comprehension.

7. Linguistics: These formulas analyze syntactics like word length, sentence length, and word difficulty, while overlooking word connotation, figurative language, or discourse markers.

8. Engagement: These formulas cannot score how a text engages readers. Factors like motivation, interest, and emotional connection can influence how well a reader understands and retains information.

9. Feedback: Readability formulas provide a one-time assessment of text complexity and do not offer ongoing feedback to improve writing.

10. Reliance on Scores: Relying on readability scores can lead to a reductionist approach to communication, where the focus is on making the text easier to read rather than making it meaningful and impactful.

Reading Research Quarterly highlighted that readability formulas account for only 40% of the differences in how well people understand the same text. Factors outside of the formulas, like the reader’s prior knowledge or work experience, play an important role.

Other Methods to Score Readability

To overcome these limitations, we can use or add other tools/methods.

1. Manual Analysis: Readability formulas do not consider the logical flow, coherence, and linking between sentences and paragraphs. You can do this manually on your text.

- Logical flow refers to how well the writer has organized ideas or arguments in a text.

- Coherence shows how well the parts of a text work together as a whole.

- Linking uses transition words and phrases, topic sentences, and summary sentences to pull everything together.

In a survey by the American Library Association, 60% of readers say they prefer texts with simpler language and clear structure.

2. User Testing: Conduct usability studies and solicit feedback from readers.

A report by the Nielsen Norman Group revealed that texts tailored to audience-specific jargon improve comprehension by up to 40%.

3. Eye-Tracking Studies: Track readers’ eye movements while they read. This data can tell you how readers process and comprehend your text.

4. Natural Language Processing (NLP): NLP and machine learning can help evaluate text readability by scoring a broader range of linguistic and contextual factors.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools can now predict readability with an accuracy of up to 70% in certain contexts, based on a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

5. Readability Surveys: Use surveys to gather readers’ perceptions of text difficulty. This can offer insights into their subjective experiences and reading challenges.

6. Expert Evaluation: Enlist linguists, educators, or subject matter experts to evaluate your text.

Experts in linguistics can identify readability issues with up to 85% accuracy, according to a study in the Journal of Language and Education.

7. Text Complexity Tools: Use software or online tools that analyze various text features, including vocabulary, sentence structure, and syntactic complexity, to provide a multidimensional assessment of text readability.

8. Checklists: Develop guidelines or checklists that analyze a range of readability factors, including structure, clarity, and audience adaptation.

An article in the Review of Educational Research suggests, “Checklists that collect user feedback can improve the effectiveness of readability scores by 35%.”

9. Adapt: Improve existing readability formulas to address their shortcomings and enhance their accuracy across different contexts and target audiences.

10. Cognitive Assessment: Measure the cognitive effort readers need to process and understand your text.

Resources

Manual Analysis:

- The Writing Center – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Offers guidance on creating logical flow and coherence in writing.

- Purdue OWL: Provides information on using transitions effectively in writing.

User Testing:

- Nielsen Norman Group: Discusses usability studies and their impact on text readability.

Eye-Tracking Studies:

- Tobii Pro: Offers eye-tracking solutions for readability research.

Natural Language Processing (NLP):

- Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK): A leading platform for building Python programs to work with human language data.

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: access the study on NLP and readability.

Readability Surveys:

- SurveyMonkey: A tool for creating and conducting readability surveys.

Expert Evaluation:

- Journal of Language and Education: studies on linguistic expert evaluations.

Text Complexity Tools:

- Readable: A tool for analyzing text complexity and readability.

- Hemingway Editor: An online editor that highlights complex sentences and errors.

- Readability Scoring System: an online readability scoring platform.

- Spanish Readability: an online readability scoring tool for Spanish texts.

Checklists:

- Review of Educational Research: For the article on the effectiveness of readability checklists.

Adapt:

- ReadWriteThink: resources on adapting and improving readability formulas.

Cognitive Load Assessment:

- Cognitive Load Theory: Provides an overview of cognitive load theory and its applications in readability assessment.

Readability formulas remain useful but don’t always see the whole picture. Sometimes it’s not just about word or sentence length. The content, its style, and the reader matter too.

Scott, Brian. “Readability Formulas: The Science Behind Reading Scales and Grade Scores.” ReadabilityFormulas.com, 28 Jan. 2025, https://readabilityformulas.com/science-behind-reading-levels/.