Robert Gunning, a renowned writing expert, was invited to speak at a writers’ conference to share his insights on effective writing. Among a diverse audience of budding novelists, seasoned journalists, and academic writers, Gunning took the stage with a warm smile.

He began by presenting two paragraphs on a large screen. The first was a single, complex sentence, winding and intricate, filled with clauses and commas. The second paragraph, in contrast, contained several short, crisp sentences—each one conveyed a clear idea.

“Which one of these do you think communicates more effectively?” Gunning asked the audience. After a brief silence, a young novelist raised her hand. She pointed out that the short sentences convey the ideas more clearly. She could understand them almost at a glance. Indeed, the long sentences looked impressive, but they lacked clarity and confused lower-level readers.

Gunning nodded, emphasizing the essence of his philosophy. “Writing isn’t about showcasing your knowledge of complex words. It’s about clear and effective communication. Long sentences have their place, but balance them with shorter ones for the sake of readability.”

He then engaged the audience in an exercise. He presented them with a dense, lengthy paragraph from a legal document and challenged them to rewrite it using shorter sentences without losing the original meaning. The audience eagerly participated; as they worked, the room buzzed with creativity.

Afterwards, participants shared their versions. It was evident that rewriting the paragraphs—based on his tips in this article—made the document much clearer and more accessible. Gunning smiled, pleased with the outcome.

“The key,” he concluded, “is not to impress with complex language or sentence structure, but to express your message effectively. Remember, clarity is king in the realm of writing. Write to express, not to impress.”

Tip #1:

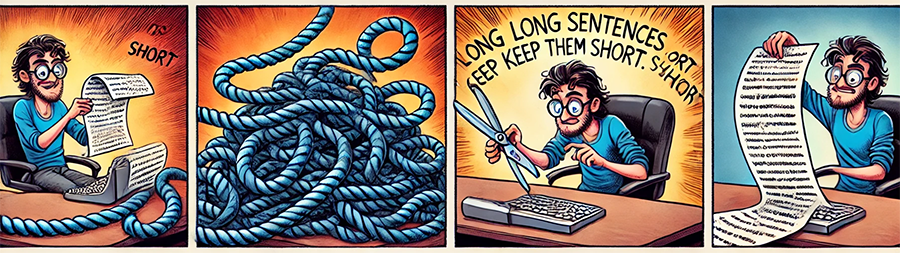

Good writing uses a rhythm of sentence lengths: long, medium, and short sentences weaved happily together; the text reads with a natural flow and maintains the reader’s interest. Too many long sentences can burden and stress readers, and too many short ones can make the text choppy. The American Press Institute suggests “sentences of 14 words or fewer are understood by 90% of readers…comprehension drops as sentence length increases.” The Gunning Fog Index, a popular readability formula developed by Robert Gunning, implies sentences over 20 words start to become less clear.

- Short Sentence: Around 10 words or fewer—perfect for when your reader has the attention span of a goldfish.

- Medium Sentence: Between 11 to 20 words—just enough to sound smart but not so much that your reader needs a coffee break halfway through.

- Long Sentence: 21 words or more—this is where you start channeling your inner Shakespeare, but be careful; your reader might need a map and a snack to get to the end!

Tip #2:

The average sentence length is a strong clue of its readability. Psychological research reveals shorter sentences reduce cognitive load because the text is easier to read. AND shorter sentences use less working memory. Writers should aim for an average (short + medium + long / total sentences) that fits their audience’s reading level and doesn’t burden them with complexity.

In his book On Writing, Stephen King highlights the importance of using short sentences to make prose dynamic and accessible.

Tip #3:

Over the centuries, sentences have trended shorter in English prose. For example, in the works of early English writers like John Milton, sentences averaged over 50 words, while today’s writers average 14-20 words per sentence. With social media growing and attention spans dwindling, readers prefer short, more direct sentences.

Tip #4:

The purpose of writing is to convey an idea, fact, or story to the reader, NOT to showcase the writer’s vocabulary or stylistic prowess. When writers focus on self-expression at the cost of clarity, the writing becomes complex, or what Gunning calls “Fog.” Clear writing must rank the reader’s understanding over the writer’s desire to impress.

If you wish to get facts and ideas across…shift the focus of attention from yourself to the readers. Such a shift encourages short sentences, the kind normally used in face-to-face conversation. — Robert Gunning

Tip #5:

“Keep sentences short” is a principle, not a hard rule. While short sentences contribute to clarity, they must balance against other writing rules. Sometimes a longer sentence is needed to convey a complex idea or maintain the narrative’s flow. Gunning suggests writers consider the context and the needs of their readers first, and then adjust sentence length.

Tip #6:

Short sentences alone are not enough; clarity is more important. Long sentences can be clear if the writer structures them appropriately and uses concrete, specific words. A clear, long sentence is preferred to a short but vague one. The key is to use every word and phrase with purpose.

Tip #7:

Abstract or ambiguous terms can obscure clarity, which Gunning refers to as “fuzzy words.” To enhance clarity, writers should choose words that convey specific, concrete images or concepts so readers find the text relatable and easier to visualize.

Tip #8:

Writers can edit out unnecessary words—especially adverbs and adjectives—to make sentences shorter and clearer.

These examples illustrate this point:

Adverb Reduction: Adverbs modify verbs but can be redundant or weak. For example, you can shorten the sentence “She smiled happily” to “She smiled.” The adverb ‘happily‘ is not needed as ‘smiled’ already conveys happiness.

Adjective Removal: Too many adjectives can clutter a sentence without adding substance. For example, you can simplify “The big, scary, hairy spider” to “The spider.” Unless the size, scariness, or hairiness of the spider is relevant, you can omit these adjectives.

Reducing Redundancies: You can shorten phrases that repeat the same idea. For example, “12 midnight” can be “midnight,” as midnight inherently means 12 AM.

Avoiding Pleonasm: Pleonasm is using more words than necessary to convey meaning. For example, you can edit the phrase “return back” to just “return.”

Simplifying Passive Voice: Passive constructions use more words than active voice. “The ball was thrown by John” can be stated as “John threw the ball.”

Concise Opening Phrases: Writers sometimes start with verbose intros, like “It is important to note that…” which you can omit for brevity and clarity.

Tightening Tautologies: Tautologies are phrases where parts repeat the same meaning. For instance, “free gift” can be “gift,” as gifts are inherently free.

Prepositional Phrases: Too many prepositional phrases can make a sentence lengthy and complex. For example, “The decision of the committee” can be tightened to “The committee’s decision.”

Filler Words: Words like ‘just’, ‘very’, ‘really’, ‘quite’, etc., add little to the meaning and can be removed. “She was very happy” can become “She was happy.”

Tip #9:

Use transition words wisely to guide readers through your argument or narrative, but don’t overuse them. Words like “however,” “therefore,” “moreover,” and “consequently” can add clarity but too many will stretch your sentences without purpose.

Tip #10:

Use active voice—it will make sentences clearer and direct than passive voice. Active constructions omit unneeded words, such as “was” or “had been.”

Example: Instead of writing, “The report was prepared by the team,” you can write, “The team prepared the report.” The active voice is straightforward. It engages the reader with clarity and immediacy.

Tip #11:

Strong, specific nouns and verbs are the backbone of clear, concise sentences. Writers can convey more with less, reducing lengthy explanations or qualifiers. A strong verb can replace adverbs, and a specific noun can negate the adjectives. This technique shortens sentences and makes reading easier.

Instead of saying “The man walked quickly,” you can say “The man sprinted,” which paints a clearer picture with fewer words. The power of precise vocabulary supports the goal of brevity and clarity.

Tip #12:

To keep sentences short in practice, break up long sentences where possible. Ensure each word carries its weight. Use one word that can replace two or three words. This approach helps to write concisely, which is important for instructional or informational text.

These examples illustrate this point:

“Due to the fact that” replaced by “Because”:

- Original: “Due to the fact that it was raining, the game was canceled.”

- Revised: “Because it was raining, the game was canceled.”

“In spite of the fact that” replaced by “Although” or “Despite”:

- Original: “In spite of the fact that he was tired, he finished the work.”

- Revised: “Although he was tired, he finished the work.”

“At the present time” replaced by “Currently” or “Now”:

- Original: “At the present time, we are not accepting new clients.”

- Revised: “Currently, we are not accepting new clients.”

“In the event that” replaced by “If”:

- Original: “In the event that it rains, the event will be postponed.”

- Revised: “If it rains, the event will be postponed.”

Tip #13:

Nominalizations are nouns derived from verbs. For example, “completion” comes from “complete,” “decision” from “decide,” and “failure” from “fail.” These nominalized forms can lead to overly abstract, passive, or wordy sentences. The key is to identify when a nominalization complicates a sentence and when it’s appropriate for the context. In some cases, using nominalized forms create a more formal or academic tone; however, opt for the verb form to make your writing more direct, dynamic, and concise.

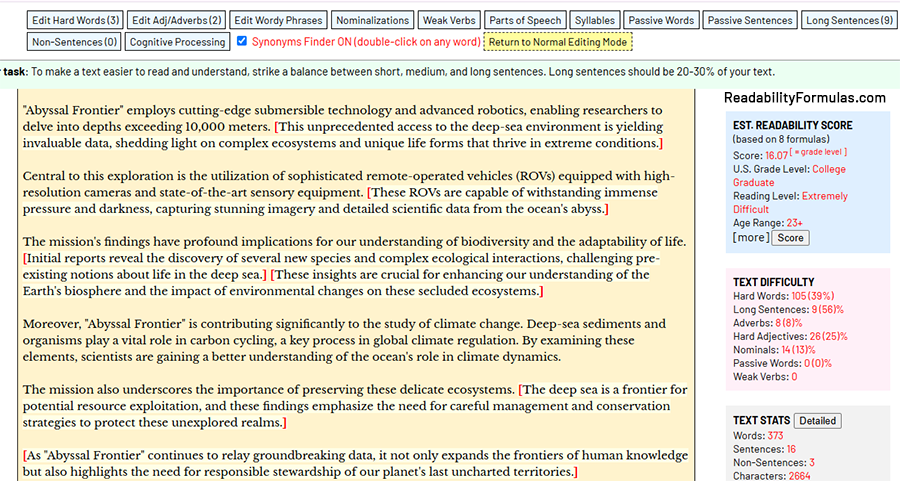

The author of the article, “Breakthrough in Deep-Sea Exploration” ignored the rules of nominalizations and overused them. This made many of his sentences long and complex. A quick edit using the Robert Gunning Editor to change the nominalizations back to their verb forms can make his article much easier to read.

Remember Gunning’s golden rule: “Write to express, not to impress—no one likes a show-off, especially in print.” Shift the spotlight from yourself to your readers. Think of it like hosting a party—your job is to make sure everyone’s having a good time, not to hog the karaoke mic. Keep it clear, keep it fun, and your readers will stick around for the encore.

Scott, Brian. “Writing Clear Sentences the Robert Gunning Way.” ReadabilityFormulas.com, 18 Mar. 2025, https://readabilityformulas.com/writing-clearer-sentences-the-robert-gunning-way/.